Competition between rail and road

In a radio address broadcast two days after he became Chancellor of the German Reich, Hitler promised the electorate to provide “work and bread”. Indeed the surprising success of his state job creation programs accounted in no small measure for the popularity of his regime. Without necessarily lending National Socialism their immediate political support, many entrepreneurs invested a great deal of hope in this reversal of economic fortunes, considered by most to have been scarcely possible. It was a moment the Knorr-Bremse Board of Management dated with great precision in its annual report: “The turning point was January 30, 1933.”

With the number of incoming orders now on the increase – the economic upturn was having a particularly marked impact on the transportation sector – the company could at last start creating new jobs. Construction of a network of freeways – the Reichsautobahnen – was perhaps the most effective of the new regime's job creation programs. It also showed beyond doubt that Hitler saw the motor vehicle as the mode of transportation of the future, according it priority over the railroads in both civilian and military life.

So the tangible economic upturn which accompanied the early days of the Third Reich led also to a marked shift in the focus of sales at Knorr-Bremse. The Reichsbahn, by far Knorr's largest customer, was awarded the commission to build the autobahns. At the same time it took on a development role in automotive design. As well as embarking on a rigorous program of expansion for its road freight delivery service, it expanded into bus transportation and became one of Germany's major commercial vehicle operators, putting into service 1,000 new trucks fitted with Knorr air brakes in 1934 alone. In this way, the Reichsbahn helped air brake technology make the desired breakthrough in road transportation, and through ongoing development work Knorr-Bremse was able to make rapid positional gains in the commercial vehicle brake sector.

Info

Reference to the content of this page

To mark the company's 100th anniversary in 2005, the history of Knorr-Bremse AG was compiled and published in a special book. The book is entitled "Safety on Rail and Road" and was written by Manfred Pohl. This book also includes a chapter on the history of Knorr-Bremse between 1933 and 1945, the time of the Third Reich (pp. 90 to 121). The content of this page of our website is taken from this chapter; the attached PDF is a scan of the original pages of the book (available in German only).

Knorr-Bremse in the Third Reich

The trend toward ever faster and heavier vehicles with payloads of up to 36 metric tons finally established the air brake with other vehicle operators as well. In 1937 Knorr-Bremse supplied approximately 22,000 brake systems for commercial vehicles and 11,000 units for trailers. By this time some 80 percent of new trucks coming onto the German market were equipped with the Knorr air brake.

Now it was time to expand the company's repair operations and the retrofitting of air brake systems. The first Knorr brake service facilities were established in late 1936, and a central parts store was set up at Frankfurt am Main. Just two years later there were 200 authorized workshops in Germany. When the hydraulic brake began to establish itself in the auto industry, however, Knorr-Bremse opted not to “jump on the American bandwagon” – as the company stated in 1936. Instead, it persisted with a hybrid “air-hydraulic” brake, which combined Knorr's own air brake technology with subassemblies from hydraulics specialists Alfred Teves (ATE) and Krupp. Knorr-Bremse's only use of hydraulics was in a hydraulic handbrake for rail vehicles.

Nevertheless, during this period of turbulent expansion in the commercial vehicle sector, sales of motor vehicle brakes (Department III) rose fourteen-fold in just four years from 1933. In 1937, for example, the department's sales totaled 11.9 million RM – more even than Department I (Mainline Rail Vehicles), which, like the rail sector in general, was by this time suffering from the Reichsbahn's ongoing reluctance to order new rolling stock, as the annual report for 1935 put it.

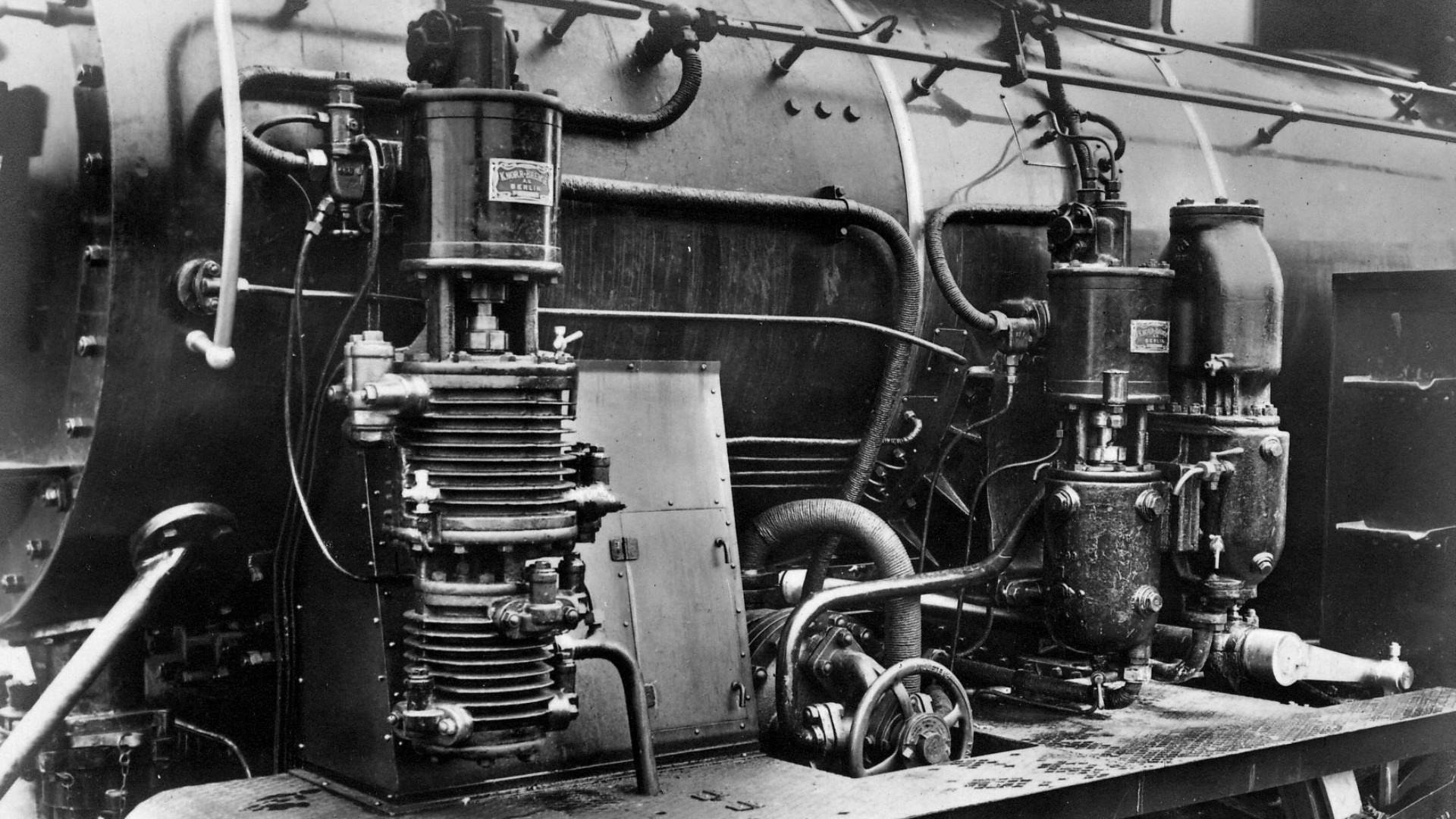

With assets of 23 billion RM and placing annual contracts worth over one billion RM, the Reichsbahn remained the “world's largest commercial enterprise” and a vital source of orders for the rail sector as a whole. Knorr-Bremse had been quick to prepare for the new technical challenges that would come to face rail transportation as a result of growing competition from the automobile and the airplane from the 1920s. The results of these preparations were not just to be found in the development of the Hildebrand-Knorr brake, which had set new standards in the mainline sector only a few years after the deployment of the Kunze-Knorr brake was completed.

The company had also pursued development initiatives in the high-speed sector. The use of brake linings promised improvements in the way braking forces were traditionally transmitted to the wheel rims. And faced with the choice between disk and drum brakes, Knorr-Bremse opted for the latter, a system it had already successfully deployed as a streetcar brake. In addition, in the high-speed sector the company began to exploit the potential of a braking system whose effectiveness was no longer dependent on the minimal grip that existed between wheel and rail:

In the early 1930s Knorr-Bremse acquired the Jores & Müller company and allocated it to Department II, which was now equipping multiple units in addition to streetcars and light rail vehicles. This small firm specialized in electromagnetic track brakes, which work by lowering magnetic shoes over the rail head which then “grip” the rail. Like the air brake, the electromagnetic track brake had already proved itself in the streetcar sector. Jores & Müller, which was to retain its own name as a part of the Knorr-Bremse Group until 1944, could also claim to have equipped the legendary “Rail Zeppelin” which on June 21, 1931 reached 230 km/h on a propeller-driven test run between Berlin and Hamburg. Although various teething troubles prevented it getting beyond the prototype stage, the Rail Zeppelin demonstrated the Reichsbahn's conviction of the need to find ways of increasing the speed of transportation.

In the ever fiercer competition between rail and road, the Reichsbahn promoted itself as the faster, more advanced mode of transportation. The speed of freight trains had risen dramatically and by the early 1930s the maximum permitted speed for express passenger trains had also been raised on a number of lines.

When the Reichsbahn turned to operating high-speed multiple units, Jores & Müller developed an electromagnetic track brake for the new car sets. It was introduced as an auxiliary brake and first entered service on the legendary Fliegender Hamburger – the diesel-electric high-speed multiple unit that attracted worldwide attention when it came into operation on the Berlin to Hamburg route on May 15, 1933 with a scheduled top speed of 160 km/h. The Reichsbahn had invested a great deal of time and effort in equipping this train with the appropriate braking system – and seats were booked up weeks in advance. The Hildebrand-Knorr brake developed in 1931 was also used on the Fliegender Hamburger.

These brakes for high-speed trains, developed at Knorr-Bremse in an astonishingly short time-frame, may not have returned high sales figures, but they nevertheless helped the Reichsbahn to achieve high-profile international successes and thereby underlined the role of Knorr-Bremse as an important development partner to what was still Europe's largest and most technologically advanced railway operator.

Knorr-Bremse also worked with the Reichsbahn to find new solutions to the German capital's steadily growing mass transit requirements. The Berlin S-Bahn, widely considered the most advanced light railway system of its kind in the world, was equipped with electrically controlled air brakes, motorized compressors and pneumatically operated doors – all supplied by Knorr-Bremse. Thanks to the foresight with which the company increased its technical staff, Knorr-Bremse was able to introduce a whole series of other innovations in the railway sector during the years that followed.

Throughout the 1930s, in addition to manufacturing the air brake Knorr-Bremse developed its activities in other product segments. In 1935, for example, the company joined with interested French and British parties to establish a syndicate with the aim of marketing the Isothermos axle bearing worldwide. In conjunction with the Walter Peyinghaus Iron and Steelworks in which Knorr-Bremse held a dormant equity holding, the company had been striving to ensure the widespread acceptance of the Isothermos bearing since 1925. With effect from January 1, 1938, the Peyinghaus steelworks based at Volmarstein in the Ruhr was taken over and became Knorr-Bremse AG, Stahlwerk Volmarstein. This left Knorr-Bremse with its own efficient foundry facility with around 1,000 employees.

Knorr-Bremse's attempts to expand into new markets centered mainly on the manufacture of pumps and compressors, which it had long designed as components of the air brake system. The company set up a new business unit – Department IV – to produce industrial compressors for applications in over 100 different fields.

A key figure in all of this was the engineer Hans Peters, whom Vielmetter had appointed in 1926 to head up the testing department. Knorr-Bremse became Germany's number one manufacturer of steam compressors. Since the mid-1930s it had also manufactured high pressure compressors such as those fitted to the whale catcher, the Walter Rau.

As a manufacturer of compressors the company also systematically developed its position. To boost sales, paint spray guns and pneumatic drills were added to the product range. For the latter, the company attempted to find a British licensee. Knorr-Bremse also supplied pneumatic tipping systems for the coal trucks used in the opencast brown coal mines. Department IV also manufactured starter clutches and transmission units under license, and with its signaling systems Knorr-Bremse also gained access to the market for automatic train control. Although these new products fell well behind brake manufacture in terms of sales, they often raised hopes of substantial new sales markets.

Then there was another production unit that initially generated little in the way of sales: Created in May 1934 as department “RB” this unit was kept strictly separate from the rest of the plant. Later also known as Department V, it was dedicated to armaments. However, trials with a patented compressed-air machine gun initially brought the company more losses than anything else.

Between global market and European “New Order”

By now Knorr-Bremse was represented in many different countries around the world. In addition to Germany these included Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Iran, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and Yugoslavia. Outside Germany, the Kunze-Knorr freight train brake had already been introduced in Sweden, the Netherlands, and Turkey and to some extent in Hungary.

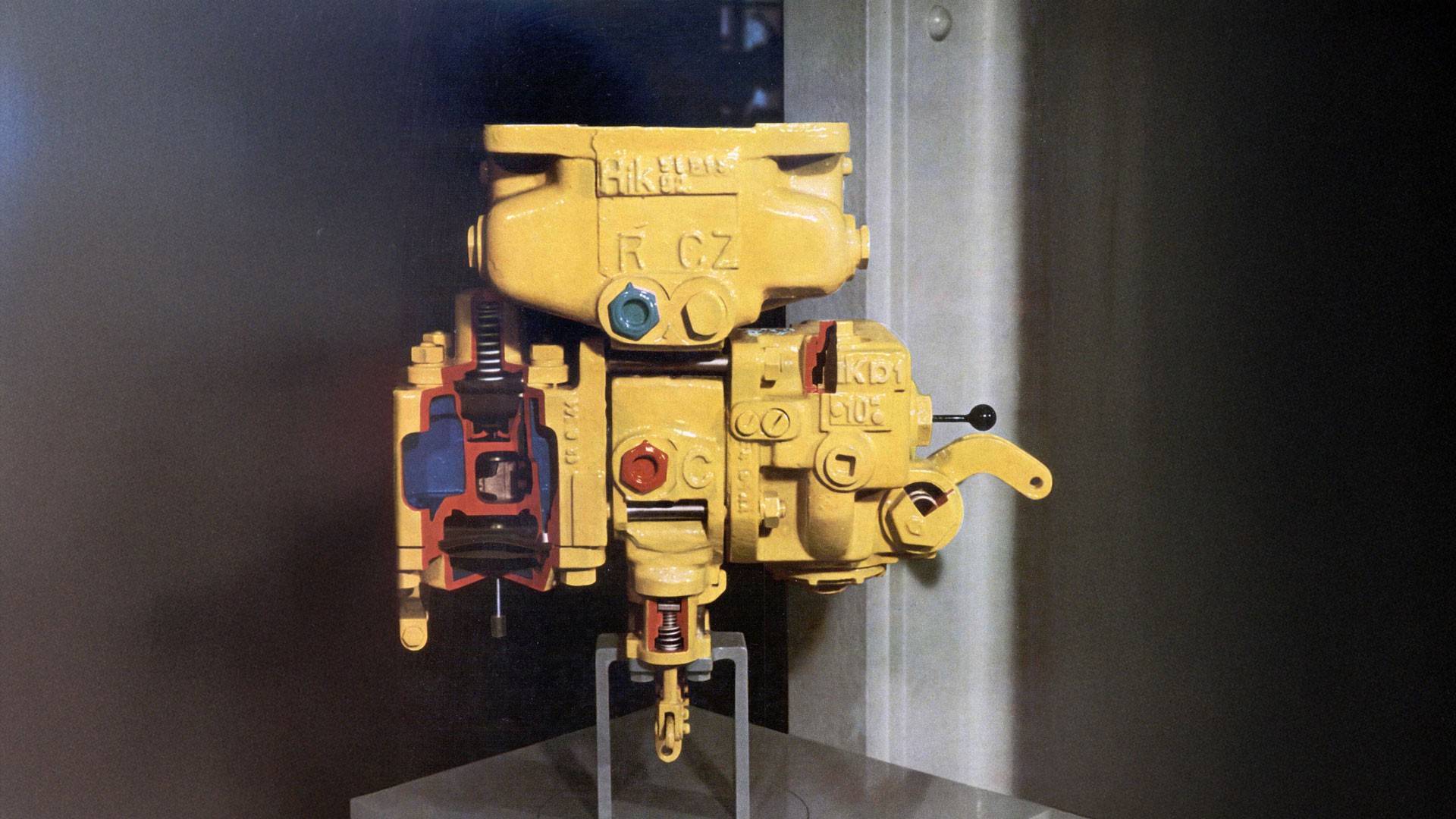

The newly developed systems for express rail transportation also soon met with interest abroad. Starting in 1936, the “lightning trains” of the Danish State Railway were fitted with both the electromagnetic track brake and the external-pad drum brake from Knorr-Bremse. Department II (Light Rail Vehicles and Multiple Units) supplied its systems to railway operators in Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia, as well as Spain, Turkey and South America. From 1937 onwards a total of 140 multiple units with Knorr brakes were exported from Hungary to Argentina. But above all it was the Hildebrand-Knorr (Hik) brake which promised a sizeable increase in foreign sales – the brake the Reichsbahn would soon be fitting to all new passenger and freight cars.

The Hik brake had already received authorization for cross-border rail traffic from the UIC in 1931. The “Hiks” rapid-action version was awarded a Grand Prix in the “safety” category at the 1937 Universal Exhibition in Paris. At this time, Knorr-Bremse was involved in promising negotiations with many foreign railway authorities, and now the company also attempted to gain a commercial foothold in South America – in direct competition with Westinghouse. In Brazil in the spring of 1938, Companhia Paulista began trials with the Hildebrand-Knorr brake on the track between Tapuya and San Carlos where the system proved particularly effective on long and heavy trains.

Like its predecessor, the Hik brake found its first foreign market in Sweden. By 1939 it had also been decided to introduce it in Norway, Austria, Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria and Iran. In Iran it was fitted to English rolling stock and went into service between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf on the Trans-Iranian Railway opened in 1938. Denmark and Hungary also decided in principle to adopt the Hik. Authorities in countries with an indigenous railway industry insisted on domestic production. But with a shortage of funds as a result of inflation, the Great Depression, and above all the strict foreign exchange controls introduced after the banking crisis of 1931, German companies found it difficult to set up their own production facilities abroad.

In Hungary Knorr-Bremse made efforts to purchase a majority shareholding in the Budapest-based Telefonfabrik AG, with whom a license agreement had been in place since 1926. But the problem of currency transfer caused the attempt to fail in 1933. In Romania, where a company called “Frana Knorr” was initially established, Knorr-Bremse ultimately concluded a license agreement with Fabrika de Lokomotiva N. Malaxa S.A.R. of Bucharest in 1936. In that same year, a license agreement was signed with Gebr. Hardy Maschinenfabrik und Giesserei AG in Vienna governing the manufacture of the Hik brake and other Knorr products for the Austrian market. Still in 1936, in Norway Knorr-Bremse assigned manufacturing rights to the Kongsberg Vaabenfabrik in Kongsberg, with Berlin to supply high-quality components such as control valves and brake cylinders at least for an initial period. And finally in Sweden Knorr-Bremse concluded an agreement in 1937 with Nordiska Armatur Aktiebolaget, its license partner since 1919. With plants in Stockholm and Lund, the company would manufacture the Hik brake for Sweden.

Not long after this, however, the politics of conquest and exploitation of the Third Reich dragged expansion of the Hik brake further and further into the troubled waters of the European “New Order” under German rule. The war meant that, on the one hand, major orders for Turkey and Iran, as well as for Estonia and Latvia were lost – countries that fell either into the sphere of influence of the western Allies or the Soviet Union. And the outbreak of war meant that all attempts to gain a foothold in South America had to be abandoned. Contacts were now necessarily focused on those railway authorities and licensees of Knorr-Bremse in the occupied states of Europe, or in neutral countries with German troops on their borders.

The ongoing joint venture with Nordiska Armatur Aktiebolaget (NAF) in Sweden remained relatively uncomplicated, however. A close working relationship had existed since 1919, and the company's Lund plant, which employed a workforce of several hundred, manufactured brake sets for the Swedish State Railway under a licencse agreement with Knorr-Bremse. That said, the company in which Johannes P. Vielmetter held a personal stake of 8 percent was certainly no easy partner. Lengthy disputes over sales rights bound up with the license agreements were not finally settled until 1936. And the new licensing agreement concluded with Knorr-Bremse in 1937 was not actually ratified by NAF until 1940. Throughout the entire duration of the war the Berlin company enjoyed a good reputation in neutral Sweden, and this made it possible for cooperation with its licensee to continue. In 1941 the first foreign company to be assigned the rights to produce and sell Knorr-Bremse brake equipment for road vehicles was also from Sweden – Thulin of Landskrona.

The annexation of regions by the Third Reich and ultimately its military conquest of large areas of Europe smoothed a path for German companies and their products into those occupied or annexed territories. In Austria, for example, following the Anschluss to the German Reich in March 1938, the decision was taken after “consultation” with the German authorities to bring the country's rail vehicles into line with German technology as quickly as possible. In spite of their license agreement with Knorr-Bremse, Gebrüder Hardy AG of Vienna had been working on the development of a new control valve, which unlike the Hik valve employed innovative rubber seals rather than metal ones. With the events of 1938 the company was forced to abandon this development and its director, the British citizen William Francis Hardy, left Austria to serve in the navy of the allied forces. The new regime put the company under the control of a commissioner, and on the basis of the license assigned two years earlier, Gebrüder Hardy finally started production of the Hik brake for the state railway, now part of the Reichsbahn. In the Netherlands and Denmark, too, it was only under German occupation that the state railways began systematic introduction of the new brake.

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the view eastwards also became distorted in the whirlpool of military force. In August 1941 the Board of Management at Knorr-Bremse AG was mistakenly convinced that an entirely new set of challenges lay ahead. “The reorganization of Europe will in all probability mean new challenges in the freight train brake sector. Longer, continuous routes will lead to greatly increased train lengths and loads, particularly if Russia were ever to be incorporated into the European transportation network.”

Part of the German regime's strategy was to exert pressure on the business sector in occupied countries, while at the same time leaving a free rein to private competition.

In the eyes of the Board of Management at Knorr-Bremse, therefore, the license agreement concluded in October 1942 with Skoda in Prague for its Adamsthal plant was considered a notable success, since until then the Prague company had been striving to distribute a competitor product, the Bozic brake. “We regard this agreement as a further major step towards the exclusive use of the Hildebrand-Knorr brake throughout Europe,” reported the Board. Not long before this, the Reichsbahn's Central Office had given its consent for Skoda to manufacture at its Adamsthal plant “all brake parts for locomotives ordered by the Reichsbahn, for which Knorr-Bremse holds no industrial property rights.” As with Gebrüder Hardy in the Ostmark region, Skoda was a key target in the Third Reich's attempt to bring commerce in the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia under German control by pseudo-legal means.

By this time the Reichsbahn covered large parts of Europe and Knorr-Bremse was receiving a growing number of orders from the Ostbahn (Eastern Railway) operated by the “General-Governorship.” At the same time, the company's Berlin plant was directly supplying the railway industries in occupied Belgium and France, which were obliged to manufacture exclusively for the Reichsbahn. Even the Westinghouse plant in Paris was now supplying equipment for the Reichsbahn made to Knorr-Bremse designs, a turnaround from the situation a decade earlier when Knorr-Bremse had equipped French State Railways with Westinghouse brakes.

There is no documentary evidence which suggests that Knorr-Bremse at any stage attempted or even had the opportunity to apply political force to obtain orders or conclude license agreements. The Board of Management actually reacted to the rapidly increasing orders from abroad with growing restraint and attempted at least to draw out their acceptance so as not to incur excessive order backlogs. Unlike many other German companies and investors, Knorr-Bremse evidently made no attempt to acquire potential suppliers in the occupied countries, even though with the growing number of orders on the books the company was obliged to subcontract to foreign operators and thus run what it perceived as a risk of future competition. Orders were subcontracted to at least 57 companies in occupied territories during the war, including 21 in France, 27 in Belgium, three in both Italy and Denmark, one in Norway and two in the General-Governorship set up in Poland.

When, however, in the summer of 1943 increased allied bombing caused the Reich's Minister for Arms and Munitions to instruct Knorr-Bremse to relocate parts of its plants to sites further east, the company did take over production facilities in Myszkow and Sosnowice in that part of Upper Silesia ceded to Poland in 1920, but which since German occupation had been reincorporated into the Reich. These were a former metal- and enamelware factory and a large textiles plant, which following German occupation had been placed in the hands of the “Haupttreuhandstelle Ost” (HTO), the Central Trust Agency, Eastern Division. But here, too, Knorr-Bremse refused to purchase the real estate and instead signed a lease agreement with the HTO. These “relocation plants” employed between 1,000 and 1,200 mainly Polish workers, but in addition part of the regular Berlin workforce was moved there in order to produce materials vital for the war effort, for customers such as the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe.

The Supervisory Board was by now receiving reports from management that spoke of “very serious pressure” being applied by the relevant committees at the Ministry of Defense whenever the supply programs they had set up were not smoothly executed. The Board of Management found itself increasingly restricted in its freedom of decision and, under mounting difficulties, forced to supply the requisite equipment to various German railway authorities, whose influence by this time extended far beyond the borders of the Reich. Orders from the Eastern Railway rose to 800,000 RM in 1942. These not only facilitated the directly war-related services provided by “the railways required for the transportation of troops and supplies,” as the annual report from the Knorr-Bremse Board of Management put it. The development of efficient railway operations in occupied Poland was also vital for the trouble-free “evacuation” of half of Europe's Jewish population to the mass death camps of the Third Reich.

One can only speculate about what Berlin company directors knew, did not know or did not want to know of such matters. But Knorr-Bremse's relocation plant at Sosnowice near Katowice, which started production in February 1944 and where some 300 workers from Berlin were also employed until just before the end of the war, was no more than 20 kilometers from the Auschwitz extermination camp. The Nazi regime hermetically sealed off its mass-murder machinery from the outside world. Anything that did reach the ears of people outside the camps was so incredible that few in Germany or abroad were able to believe what they heard until allied troops were able to reach the camps and free the few remaining survivors. Whether or not the truth was known, no trace of it found its way into the surviving records.

Knorr-Bremse in the wartime economy of the “Third Reich”

Legislation passed on February 10, 1937 placed the Reichsbahn under the direct sovereignty of the Reich and thus under the control of the regime. From that point on it became known officially as “Deutsche Reichsbahn.” The new Reichsbahn Law introduced on July 4, 1939 expressly placed the transportation company at the service of “national defense requirements.” The expansion of its rolling stock however trailed far behind the growth of the Reich's production of actual armaments. At the outset of the war, Johannes P. Vielmetter had expressed the conviction “that construction of rolling stock is as vital to the war effort as the manufacture of any kind of weapon.” Not only was he soon proved correct, but his opinion also was shared by the military administration charged with fixing production quotas and the allocation of raw materials to industry.

In 1940 the Berlin production facility turned out a monthly average of 4,000 Hik freight and passenger car brakes for the Reichsbahn and for export. And in early 1941 its Munich subsidiary Süddeutsche Bremsen began supplying 1,500 Hik control valves to the Reichsbahn per month, with production rising to over 2,000 valves per month by the end of the war.

In 1942, control of production was placed directly in the hands of the new Reich Minister for Armaments and Munitions, Albert Speer, who set up a Central Committee for Rail Vehicles. As a direct consequence of this, Knorr-Bremse was required to boost production by roughly 80 percent, primarily in the locomotive equipment sector. Taking into account the relocation plants at Myszkow and Sosnowice and the Munich subsidiary, during the latter years of the war Knorr-Bremse produced 500 complete brake sets for locomotives every month, in addition to a daily output of 250 Hik brakes mainly destined for freight cars. All in all, sales for Department I (Mainline Rail Vehicles) rose by a factor of six between 1937 and 1943, from 11.8 million RM to 72.6 million RM. In Department III (Motor Vehicle Brakes) the decline in civilian orders at the outset of war was offset by increased incoming orders for expanding military fleets. Sales of commercial vehicle brakes, however, which had been growing exponentially in the run-up to the war, became increasingly affected by restrictions on raw materials for the automotive industry and went into decline having reached a high point of 18.7 million RM in 1941.

The armaments department at Knorr-Bremse also acquired a new significance during the war, as the company turned out large numbers of compressors for airplanes and for the navy. In addition, Knorr-Bremse supplied substantial numbers of barrels for anti-tank artillery and shells to the army. During the war years, Department RB employed a workforce of about 400. Knorr-Bremse was also involved in a whole range of military development projects. Towards the end of the war, for example, two employees were working at the Peenemünde rocket center designing air-sprung brake sleds for launching the V1 rocket, the so-called “vengeance weapon” – although these were never brought into use. But even during the war, revenues from the armaments department represented a relatively small proportion of total company sales, hovering on average around the 6 percent mark and reaching a record high of 13.3 percent in 1942. For the entire duration of the war Knorr-Bremse remained at virtually full capacity with the production of air brakes for motor vehicles and for rail vehicles in particular, very much in line with the portrait of the company that had appeared in Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung on June 27, 1935: “Knorr-Bremse A.G. became established as a brake manufacturer, and this branch of operations will always remain the backbone of its industrial activities.”

At the company's subsidiaries that was not the case. Süddeutsche Bremsen in Munich took a long time to recover once the production program for railway brakes – reintroduced for a short period in 1934 to handle reparations supplies to Belgium – was brought to an end. No longer compatible with market requirements, its engine range attracted few orders. The turning point only came at the beginning of 1937 when, with assistance from Johannes P. Vielmetter, the company tendered for orders from the Army Weapons Office (HwaA) and began supplying detonators and shells. In 1938 Südbremse also began manufacturing aircraft engine parts for the Reich Air Ministry. When war broke out, the company's engine building department, which had been laboriously expanded, was also geared to supplying the army.

In Munich, actual production of armaments was seen from the outset as a stopgap measure which should be accorded no more space than was absolutely necessary. When Südbremse also took up production of Hik control valves in order to relieve the pressure on its parent company in 1941, and the Board of Management at Knorr-Bremse showed a renewed and lively interest in the production situation at its Munich subsidiary, the company even found it necessary to apologize for its ongoing production of armaments. The justification offered by the Board of Management at Südbremse was that without prewar armament production they would never have got the plant back up to capacity. The Munich company was of course aware of the drawbacks of having many and diverse products aimed at industry and agriculture, at the army, the navy, the air force and the railways. “But perhaps nowadays,” management argued in July 1941, “and in the near future it could prove advantageous not being tied to any one product.”

At Südbremse's sister company, MWM in Mannheim, too, army demand drove sales to record levels while the onset of war led to civilian orders being cancelled. Extensions to the plant were begun in 1938 and their scope increased several times, so that soon after the outbreak of war the number of employees had passed the 2,000 mark. Yet in spite of all this expansion, engine production at the Mannheim plant was constantly at full capacity.

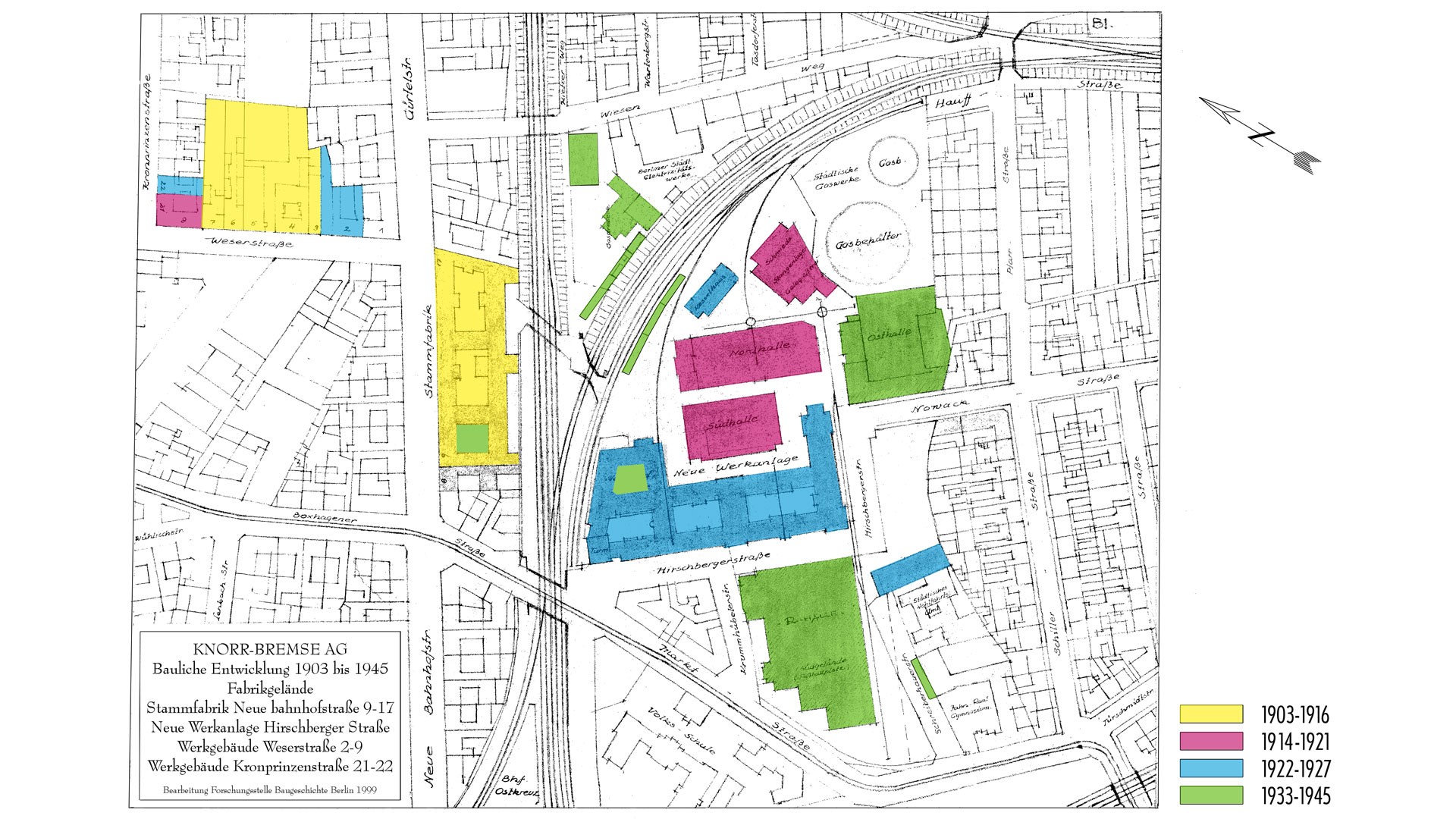

The defense boom also had a significant impact on Carl Hasse & Wrede GmbH, in which Knorr-Bremse now held a 75 percent stake. In the early 1930s, company management was quick to recognize the onset of a worldwide buildup of arms and saw an opportunity to recommence supplies of complete special-purpose machines. As early as 1930 the Reich Army Weapons Office (HwaA) had commissioned Hasse & Wrede in strictest confidence to develop a shell lathe with tools for cutting hard metal. From the mid-1930s onwards large-scale orders were obtained from mainly state-run companies throughout Europe and South America. In 1935 the company opened its own representative offices in Shanghai and Tokyo.

Since export deals meant receipts of foreign currency, which were in short supply, the Reich authorities were favorably disposed toward the company's efforts. In 1937, Hasse & Wrede were authorized to set up a pilot production facility with machinery for manufacturing shells and detonators which they were also permitted to demonstrate to potential customers outside Germany. To this end, the company acquired the site of a former iron foundry in Berlin-Britz from Knorr-Bremse, and after extensive conversion work the pilot plant, known as Plant IV, went into operation in 1938. By this stage the company's workforce had increased tenfold since 1933 and numbered over 4,000 employees. As in the past, a large part of the machines were exported, mainly to the Soviet Union. Annual sales rose from a low point of 1.3 million RM in 1932 to a high of 23.6 million RM in 1938.

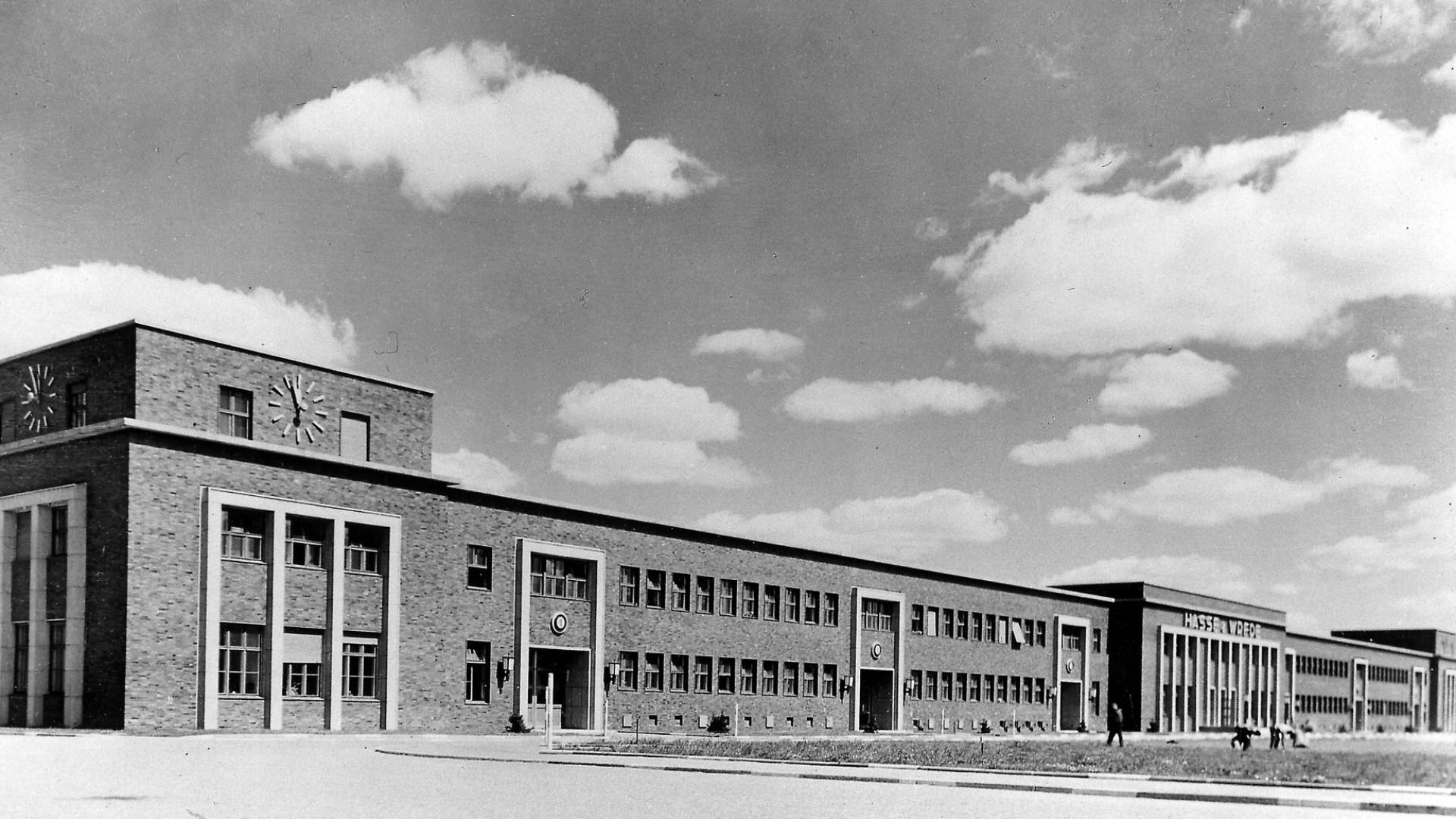

It was then decided to relocate the company's entire production operations to spacious new premises. On November 25, 1938, the Board of Management of Hasse & Wrede were invited to the offices of Albert Speer, the General Buildings Inspector of the Capital of the Reich, later to be Minister for Armaments. He allocated them a construction site in what was listed as Industrial Area 15 of the General Buildings Inspectorate near Marzahn, to the north-east of Berlin city center. The new plant, which incorporated an existing skeleton structure put up for the Reichsbahn, was built at impressive speed and under the direct supervision of the General Buildings Inspectorate.

On the day before the topping-out ceremony on August 31, 1940, acting on behalf of Hasse & Wrede, the company's directors, Paul Peter and Wolfgang Anger, signed a confidential agreement with the German Reich, represented in this instance by the German Army's Supreme Command (OKH). According to the terms of the agreement the company was obliged to make the new production facilities available when necessary for purchase orders received either directly or indirectly from the OKH. In return, the Reich would contribute 4.9 million RM to the construction costs. At the same time, the share capital of Carl Hasse & Wrede GmbH was increased from 4 million to 5 million RM, and Knorr-Bremse's stake rose to 90 percent. By March 1942 the move was complete, but in addition to operations at the giant new plant, production also continued at the Britz facility.

The Board of Management of Hasse & Wrede had asked the General Buildings Inspectorate to nominate a suitable architect specifically for this large-scale industrial construction project. The external appearance of the red brick and concrete structure picked up on the distinctive Modernist styles of the 1920s and 30s. Behind the brick-clad façade was a production hall measuring 200 meters by 200 meters. An uninterrupted 40,000 square meters of floor space accommodated 1,400 state-of-the-art machines and the 4,000 employees who operated them.

Such massive expansion in the interests of the defense sector called for considerable investment. A total of 24.5 million RM was poured into the new Hasse & Wrede plant at Marzahn, most of which was financed through credit agreements. In a development described internally as “not wholly without risks,” the company, whose senior director Julius Wrede died on February 23, 1939, had surrendered its independence. “Developments to the plant have made Hasse & Wrede the largest machine tool factory in Europe, perhaps even in the world. Following this expansion, carried out at the orders of the Supreme Command, Hasse & Wrede's capacity now exceeds that of normal machine tool factories. Once the war is over, utilizing this capacity to the full will be an enormous challenge.” The plant was therefore fittingly described a “shadow facility of the defense industry.”

By the end of 1939, Knorr-Bremse and its subsidiaries employed a workforce of over 20,000. The armaments boom had led to extraordinary expansion at the subsidiaries. But the dangers of this growth, occasioned to a large extent by the political framework conditions, were clearly recognized. For this reason the management of Knorr-Bremse was at pains to avoid any excessive expansion of capacity at the parent company. In summer 1938, Johannes P. Vielmetter made the following statement to the Supervisory Board: “We are not keen to undertake any expansion of our existing facilities; instead we are intending to engage the cooperation of plants with which we have friendly relations.” This was to remain the company's strategy throughout the war years. Once production capacities at Südbremse were fully stretched, the demands imposed by the war economy were seen increasingly as a burden. A large delivery backlog meant the risk of orders going to competitors, and in such cases this also meant handing over technical drawings and vital technical know-how.

The company's relationship with its number one customer was also encumbered by pressures of a rather different kind. Supplies to the Reichsbahn had traditionally been calculated on a “cost-plus” basis. The company submitted its audited cost accounting to which it was then permitted to add a limited profit margin. At times, prices were appreciably higher than production costs, so that the considerable costs of development could also be covered. But during the war this costing basis was abandoned in favor of a rigid fixed price system. From 1940 the Reichsbahn cut prices considerably on numerous occasions. Johannes P. Vielmetter saw his company reduced, as he complained in a letter dated June 22, 1940 to the Berlin Central Office of the Reichsbahn, “to the level of a screw factory.”

Knorr-Bremse nevertheless sought to honor delivery promises, come what may, right up to the end of the war, in spite of falling or even non-existent earnings. But this should not be ascribed to the considerable pressure exerted by the armaments committees alone. The company also kept a clear eye on the post-war situation. “It is vital,” explained the Board of Management in March 1943, “that our company should not lose these orders, as we shall otherwise see the development of competition that would not only help to meet the extraordinary growth in demand occasioned by the war, but would also pose a competitive threat to us in later years in both domestic and foreign markets.” Consequently no distinction was made between the demands of war and the interests of the company.

Responding to the substantial problems encountered not least in the field of human resources, the Board squared up to the need to restructure production operations and remained determined to meet its supply obligations. In its report of early 1943, management stated:

“Failure [to meet our obligations] would bring untold consequences both for the conduct of the war and for our company. The required increase in productivity has repercussions upon internal company structures in particular, since there are no more skilled workers to be had and the gaps that arise as a result of conscription cannot be adequately filled.”

From full employment to forced labor

For the workforce at Knorr-Bremse the economic upturn since 1933 had brought tangible improvements in terms of wages and benefits. But even before the outbreak of war the company encountered occasional staffing shortages – despite the workforce having risen again to nearly 5,000. Now that there was full employment, the shortage of workers – above all skilled workers – was very much in evidence. Company management attempted to overcome the problem by introducing retraining programs, using machinery to cut manpower needs, and restricting the volume of administrative work. For some time there had been a growing trend towards appointing female staff. The number of female workers and employees at Knorr-Bremse rose four-fold between 1933 and 1938 from 149 to 621, while in the same period the total number on the payroll little more than doubled from 2,152 to 4,925.

As the war progressed, the need for additional workers grew steadily as more and more employees were called up to the armed forces and production requirements continued to rise. By the end of the war, the proportion of employees from the Knorr-Bremse parent company in Berlin who had been conscripted or had fallen in the war rose to more than two thirds of the male German workforce. The solution of filling vacancies with growing numbers of female and untrained workers quickly reached its limits. Conditions of employment became increasingly strict. From the summer of 1941, for example, repeated unexcused absenteeism could be punished not only by dismissal but by a prison sentence of up to three months. Even so, the drain on human resources constantly threatened to interrupt production.

In order to guarantee wartime production, the Nazi regime ruthlessly appropriated labor in occupied countries. Many volunteered for employment out of sheer desperation. But there were nowhere near enough such volunteers, and increasingly people were brutally dragged from their home countries and forced to work in German factories. Prisoners-of-war were also subjected to forced labor. While this was permitted under international law, it often took place under catastrophic circumstances. In August 1944 there were a total of 7,615,970 foreign workers registered within the territories of the Greater German Reich.

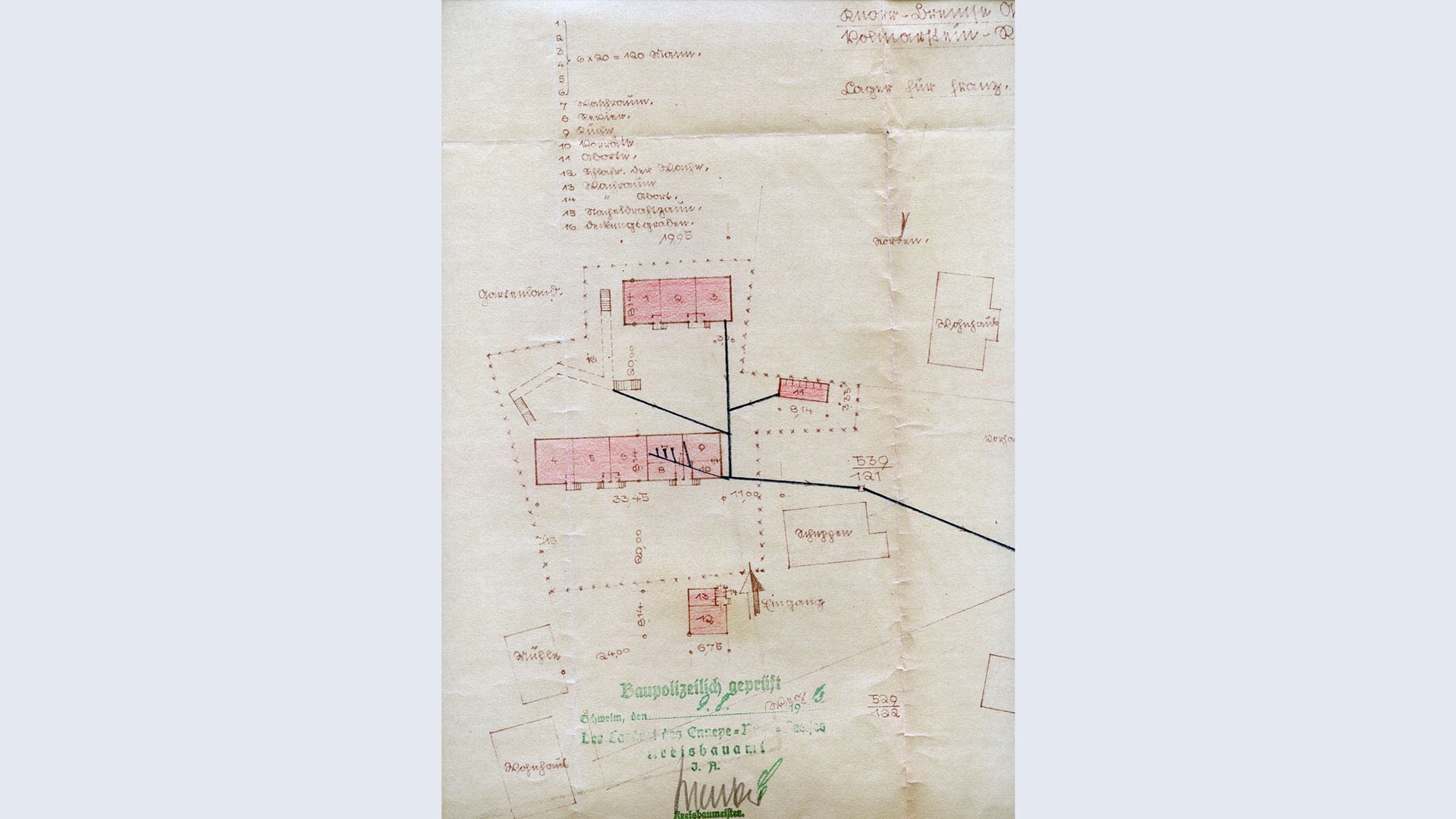

For the companies themselves, however, such employment often brou^ght additional problems, such as the obligation to provide food and accommodation. Like many other companies, Knorr-Bremse and its subsidiaries employed large numbers of foreign workers. At the meeting of the Supervisory Board on March 4, 1943 the Board reported that “the increased use of foreign labor, mainly workers from the East and from France, necessitated the setting up of barracks built to official specifications. These camps were constructed partly by ourselves, partly by the Reich, and handed over to us for use on a rental basis. [...] They accommodate approximately 2,700 foreign workers.”

That same month the number of foreigners employed at Knorr-Bremse's Berlin parent plant reached its wartime peak of 3,101 – or 42.3 percent of the entire workforce of 7,334. Among manual workers the proportion of foreigners was as high as 48.7 percent. At the relocation plants in the General-Governorship, the workforce was mainly Polish. When these workers are also taken into account, the number of non-Germans employed in July 1944 peaked at 4,090, at a time when Knorr-Bremse employed a combined total workforce in Berlin, Myszkow, and Sosnowice of 8,269. Similarly, at Südbremse, where the workforce would soon reach 2,000, up to 50 percent were foreign workers, including French and Soviet prisoners-of-war. In individual production departments the foreign workers even accounted for as much as 75 percent of the workforce. At the Volmarstein Steelworks 100 prisoners-of-war were employed as early as 1940. By September 1944, out of a total workforce of 1,285 the number of foreign workers there had risen to 344 and prisoners-of-war to 273.

The numbers reveal little about the circumstances under which the foreign laborers worked and lived. Above all, these circumstances varied enormously depending on a workers's country of origin. A list drawn up on July 11, 1942 for Knorr-Bremse's Berlin parent plant shows foreign workers from 19 different countries, including so-called “Eastern workers” from the Soviet Union, as well as Belgians, Czechs, Italians, French, Yugoslavs, Croats, Dutch and Poles. Many of the Eastern workers in particular were women. Prisoners-of-war were also forced to work at the plant. On the whole, Western Europeans enjoyed a degree of flexibility in their working conditions and in general were given better jobs than those from the East, who were subject to particularly severe restrictions.

In a memorandum circulated in June 1942, the Knorr-Bremse plant management maintained that the Eastern workers had “voluntarily offered their services.” It went on, however, to warn the German members of the workforce that “Workers belonging to an enemy power shall not enjoy any form of liberty,” and advised them to “keep a close eye on them to prevent their escape.”

All company employees were obliged to wear badges of different colors on their clothing for identification purposes. Foremen wore a white badge, German employees blue, foreign workers red and Eastern workers green. The foreign workers were also divided up by nationality before being assigned to a camp. Female Eastern workers were brought to the plant each day under guard. As at Knorr-Bremse, each of its subsidiaries maintained a camp on its own premises. The foreign workers were probably also kept segregated from German employees as they worked, with any contact limited to essential instruction or supervision by specially appointed staff. Female Eastern workers were given training in operating the lathes. The treatment foreign workers received varied enormously, from often extremely rough handling by supervisors, to individual gestures of kindness from German colleagues.

Initially the Group companies did their best to draw on every last reverse of the ever more strictly regulated labor market. At Südbremse, for example, the Board of Management requested the allocation of more female German workers, but the municipal employment office was not in a position to satisfy demand. In May 1943, the Board of Management reported to the Supervisory Board: “By taking on foreigners from many different countries and additional prisoners-of-war we were able to largely offset the shortage of unskilled labor, but there is still an acute shortage of skilled workers.”

The accounts department at Knorr-Bremse calculated a downturn in sales from 1943 onwards not just per capita, but also per wage unit. This they attributed to the use of foreign workers, despite the fact that these were paid – in line with very precise regulations – less than German workers. Hasse & Wrede reported a drop in overall sales for 1942 occasioned by the increased departure of skilled workers and their replacement by foreign workers.

Although the companies were not exactly queuing up to employ foreigners, they saw it as necessary and thus complied with a system based on the ruthless exploitation of these people. The extent to which the thinking of the despots and tyrants of the Third Reich had by this time penetrated the seeming normality of everyday working life is evident in a report sent by the Board of Management of Knorr-Bremse to the Supervisory Board on the employment situation at the Volmarstein Steelworks:

“[...] The annual average for 1942 showed 30 apprentices in training as compared with 32 the previous year. In late March of the financial year under review, 120 Soviet prisoners-of-war were brought in, of whom 75 were still working by the end of the financial year. The Soviet prisoners-of-war were in a very poor state of health, which meant that after only a few weeks or months many were forced to be retired on the grounds of sickness or death.”

Risks and omissions

The vague and confused anti-capitalist tendencies within the National Socialist ideology and movement quickly gave way upon Hitler's seizure of power to a more pragmatic approach in the interests of economic stability. On the other hand, the racist ideology of the new regime had an immediate impact, having set as its goal the expulsion of Jews from German commerce and society. As one of Berlin's most respected Jewish entrepreneurs, Isidor Loewe had helped launch Knorr-Bremse to success and a member of his family had sat on the Supervisory Board until 1932. But at the time of Hitler's seizure of power the Knorr-Bremse group employed few Jewish employees in high-ranking positions.

One long-serving female employee at Hasse & Wrede, Käthe Jacobi, who had latterly been responsible for the company's entire cash management, was told on October 21, 1935 that she could no longer remain a company employee on account of her being a Jewess. In February 1937, Wilhelm Strauss, the Jewish Board Member at Süddeutsche Bremsen in Munich, stepped down from his position, although it is no longer possible to establish the extent to which political pressure played a role in his decision. According to one subsequent account, Strauss's departure was Vielmetter's response to a demand from the Nazi German Labor Front (DAF). In any event, there is no evidence of any anti-Semitic sentiment on the part of company management.

Both Käthe Jacobi, who sought the personal intervention of Johannes P. Vielmetter, and Wilhelm Strauss continued to receive financial support from the companies they had worked for. Herbert Waldschmidt, who had joined Strauss on the Südbremse Board of Management in 1934, continued to employ a non-Aryan secretary and was thus able to protect her from persecution until shortly before the end of the war. She, like Strauss, who managed to emigrate in good time, was able to resume working for the company again after the war. In Nazi terminology Julius Wrede's son-in-law, the former company director Günther Beling, was a “half-Jew.” Yet on May 2, 1933, he was voted onto the Supervisory Board of Carl Hasse & Wrede GmbH to replace the late Walter Waldschmidt, and retained his seat for the entire duration of the Third Reich.

Political pressure was not just applied from the outside, however. Knorr-Bremse was among the first major companies to witness the development as early as 1927/28 of Nazi Betriebszellen or “factory cells” within the workforce. When Hitler's regime seized power, the works constitution was amended accordingly. The German Labor Front took the place of the trade unions, the elected Works Council was replaced by a “Council of Trust” (Vertrauensrat), and the imposition of “state labor trustees” put an end to free collective bargaining.

The new “Law on the Regulation of National Labor” of January 20, 1934, required Knorr-Bremse to draw up a new company structure, in which Johannes P. Vielmetter assumed the role of Betriebsführer (company leader) vis-à-vis his Gefolgschaft (followers). Attempts by the DAF to anchor the Nazi Führer Prinzip within the corporate structure ultimately came to nothing, but it did provide hoards of denunciators and careerists with ample scope for politically motivated attacks.

With his application of September 10, 1937, Johannes P. Vielmetter became an official member of the Nazi Party, the NSDAP. It can hardly be concluded from this, however, that the company was drawing closer to the Führer's party, and for its part the party made it quite clear who, in its opinion, was lacking the requisite “exemplary attitude”: The application of technical director Wilhelm Hildebrand, dated December 8, 1939, was turned down, as was that of authorized signatory and export director Reinhard Burkhardt on June 3, 1941. Burkhardt was accused by the party judiciary of previously having openly kept his distance. In Munich, Herbert Waldschmidt joined the Nazi party in 1937. And Wilhelm Holzhäuser, successor to Wilhelm Strauss on the Board at Südbremse, also became a member, although on account of his earlier association with a Freemasons' lodge his application was only granted five years later by “special authorization.”

The issue of management succession at Knorr-Bremse also became mired in these murky political waters. Since its establishment the company had always borne the hallmarks of a family enterprise. And while the firm had been converted into a public limited company in 1911, with its shares tied up in a syndicate to facilitate the stock market flotation that was at least considered with a view to facilitating expansion, the company never actually went public. The turbulent developments of the 1920s had forced Knorr-Bremse to become an owner-managed company. When Wilhelm Hildebrand gave notice to terminate the syndicate agreement in 1941, Vielmetter was the majority shareholder of Knorr-Bremse with 87.3 percent of share capital.

By this time, the company had once again hit stormy waters, though on this occasion they were rather different to the problems thrown up by the economic crisis successfully navigated ten years earlier. The ever-rising production demands could only be met with difficulty and at considerable financial cost. Loans raised from Deutsche Bank had already grown to almost 11 million RM by the start of the war and were a matter of grave concern for the bank's Board of Management. One strategy in such situations was to form alliances with robust – or supposedly robust – partners. This was the case with the merged Gesfürel and Ludw. Loewe & Co. AG, whose merger with the mighty AEG was agreed on February 19, 1942, leaving Vielmetter with a seat on the Supervisory Board of AEG. But Vielmetter would not even consider such a move for his own company, nor did he take steps to hand leadership of the company he had steered with increasing autocracy since 1907 to a new helmsman. The Supervisory Board, however, had been discussing the issue of management succession for some considerable time. At the outbreak of war, Johannes P. Vielmetter was 79 and Wilhelm Hildebrand 70. The Board's technical director could look back on 40 years of service in the development of the rail vehicle air brake, a period stretching back so far that he had even played a decisive part in developing the Kunze-Knorr brake.

With a clearly political agenda, Vielmetter decided in 1937 to make a new addition to the Board of Management of Knorr-Bremse AG. The new Board Member, Oskar Maretzky, had been known to the company since 1912 in his capacity as Mayor of Lichtenberg. Having been dismissed from this position on account of his support for the Kapp putsch against the Weimar Republic in 1920, Maretzky had then sided with the new regime after Hitler's seizure of power. He was subsequently appointed Lord Mayor of the Reich capital. He ran his office as a shop window for the administrative competence of the regime, but had no real political influence.

When independent local authority administration was abolished in 1937, he was forced to relinquish his office and entered the service of Knorr-Bremse, where he was appointed to the Board of Management early in 1938. The retired mayor enjoyed Vielmetter's confidence and represented the company in negotiations with the Reichsbahn. However, his appointment proved to be a mistake, since far from protecting the company from external political influences, he began plotting against its management. According to his own records, in 1940 he made the “trustees of labor” apply “sharp pressure” to Vielmetter to force him to give up his position as Betriebsführer.

And now the company's Council of Trust too went on the offensive. On November 7, 1940, it called upon Vielmetter to dismiss the human resources director and other politically recalcitrant employees who refused to carry out their duties “in the name of National Socialism.” Vielmetter relinquished the position of Betriebsführer on December 16, 1940. He was replaced in this uncomfortable role by Hellmuth Goerz, until then managing director of the Volmarstein Steelworks, who thus became a Member of the Board of Knorr-Bremse AG. Maretzky left the company in January “on amicable terms.”

Political pressure had now increased appreciably. At the same time, the impact of the war economy on the company was growing steadily. Now, though, it was no longer possible to ignore the fact that the company was increasingly lacking a firm hand on the rudder. On February 28, 1943 Wilhelm Hildebrand stepped down from the Board of Management. He was to die on December 24, 1943 at the age of 74.

Upon his departure three new members were appointed to the Board. Hildebrand's son and former assistant, Friedrich Hildebrand, was given a seat. So too was Kurt Anhalt, who like Hildebrand junior had been involved in the company for almost twenty years and had been instrumental in establishing Department III (Motor Vehicle Brakes). He was married to the widow of Johannes P. Vielmetter's late son. The third new Board Member was Alfred Woeltjen, who had only recently joined Knorr-Bremse in November 1942 in a technical management role. Woeltjen, an engineer, had been employed since 1934 at the Technical Office of the Reich Air Ministry under Hermann Göring.

Under mounting political pressure, Johannes P. Vielmetter finally stepped down from the Board in 1943, having initially taken on the newly created role of Chairman of the extended Board of Management. Once again Oskar Maretzky had plotted against him and denounced him to Gerhard Degenkolb, director of the Central Committee for Rail Vehicles (HAS) at the Reich Ministry for Armaments and Munitions, for alleged weak management as a result of old age.

The new Betriebsführer Hellmuth Goerz sat on the Brakes subcommittees of the body created in 1942 to control production, but such positions carried little political weight. Nor did they even guarantee the usual influence in defining technical standards. The aim of his presence on the committees was above all “to avoid our supplies being controlled by outsiders.” Not for nothing was Degenkolb known to his minister Albert Speer as the “absolute dictator” of rail vehicle manufacturing. Degenkolb had instigated a study which found that production output at Knorr-Bremse lagged behind that of comparable plants. Thus Maretzky's denunciation was only an ostensible reason to set in motion the events that followed.

In the end it had less to do with ideology, and more with the efficiency-oriented technocracy of the Ministry of Armaments that Johannes P. Vielmetter was forced to give up management of the company. At a meeting with the Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Knorr-Bremse, Speer's general adviser Karl Maria Hettlage demanded that measures should finally be taken to bring about the resignation of the Chairman of the Board of Management “without creating a fuss.” With that, after over 36 years on the Board, Johannes P. Vielmetter stood down as Chairman on September 15, 1943. At the same time Otto Leibrock was appointed to the Board, a man who like Friedrich Hildebrand and Kurt Anhalt had joined the company in 1924, having served as legal officer, head of the economics department and assistant to Vielmetter.

The fact is that, more recently, the company patriarch had progressively slackened his grip on the reins. Once a tightly run organization, under the pressures of the war economy Knorr-Bremse was now showing a serious lack of coordinated leadership. Latterly, even Vielmetter's secretary had held a sort of departmental sovereignty, which – according to the Supervisory Board at least – had cost the company millions. Soon to relinquish all responsibility, the departing owner-manager sought a solution to Knorr-Bremse's problems by placing at its helm a man equipped with far-reaching powers. Despite many objections, Vielmetter insisted upon appointing Alfred Woeltjen Chairman of the Board of Management “with a casting vote in the event of differences of opinion.”

But even with these new powers, Woeltjen was unable to bring the increasingly ailing company under firm rule. Responsibility for the progressive drop in output together with the financial crisis this meant for Knorr-Bremse was primarily laid at his door. And when, on May 6, 1944, the Honorary Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Knorr-Bremse Johannes P. Vielmetter died aged 84, just a few months after his departure from management, the situation escalated out of control. In vain the new production manager Walter Nase called for an end to the “all-out in-fighting.” In May 1944 responsibility for company finances was removed from Woeltjen's remit. But protected by Vielmetter's legacy, the now isolated Chairman stubbornly clung on to power until he was unceremoniously ejected from his office on April 13, 1945. By that time, Berlin was under constant bombardment from Soviet artillery.

Behind the personal conflicts, a troubling development was taking a firmer grip on the company as the war progressed. Despite the growing shortage of workers and raw materials, Knorr-Bremse had managed to increase production continuously up to 1943. Total company sales rose from 41.3 million RM in 1938 to 98.2 million RM in 1943. But in autumn 1943 bomb damage and necessary relocations brought about a progressive decline in output and thus in sales. This forced the company into a financial predicament. To make matters worse, substantial amounts owed by customers were proving impossible to obtain. Knorr-Bremse's debts with Deutsche Bank were taking on ever more alarming proportions. Given the economic backdrop, these problems may not have been able to precipitate far-reaching consequences, but in August 1944 Deutsche Bank in the person of Supervisory Board Chairman Fritz Wintermantel informed the Board of Management that it was not prepared to extend any further lines of credit in addition to those already fully taken up by the company. Research and development work, the lifeline for the future of the company, was also proving more and more difficult to perform.

Knorr-Bremse was also being directly affected by the events of the war. Since the beginning of 1943 the Berlin plant had been repeatedly hit in air raids. On May 8, 1944 one such raid cost 11 lives and injured well over one hundred employees. Nor were the group's other companies spared bomb damage. During an air raid on the night of March 8–9, 1943, 600 incendiary bombs rained down on the Südbremse premises, destroying among other things the engine test rig. And 50 percent of the branch operation of Hasse & Wrede in Britz was destroyed by incendiary bombs on January 30, 1944.

Growing threats to the plants resulted in feverish attempts to identify potential facilities to which operations could be transferred. As late as November 1944 a move was considered to the world-famous Meissen porcelain factory, but this was ultimately rejected on the grounds that the premises were too cramped. And fortunately for the company, proposals to relocate production to the vacant rooms of the Dresden museums also came to nothing. The great city on the River Elbe was destroyed by the Allied air forces in the night of February 13–14, 1945. Süddeutsche Bremsen by contrast found shelter closer to home as it sought to escape the hail of bombs that rained down on German cities in the latter years of the war: The company set up Plant II, building pumps for aircraft engines, in the vacant beer cellars of the Franziskaner Brewery.

But with the advance of the Red Army and the capture of its relocation plants at Myszkow and Sosnowice Knorr-Bremse lost its most valuable machinery. On January 20, 1945, 300 Berliners and 100 foreign workers set out from Sosnowice on a 10-day march back to Berlin. There, despite express orders to the contrary, thoughts were turning to the possibility of a transition to peacetime production and hopes were being pinned on selling the company's pneumatic drills. However, at a meeting held on March 12, 1945, the Board decided to remain in Berlin even if the city was to fall into the hands of the Red Army. The heavy machinery was not as easy to transport westwards as, for example, securities from the safe deposit vaults at Deutsche Bank, which had just decided to set up replacement headquarters in Hamburg.

The bank's Board Member Fritz Wintermantel had become Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Knorr-Bremse AG on the death of Gustaf Schlieper in 1937, and Johannes P. Vielmetter had made him executor of his will. With production now being interrupted with growing regularity by the air raid sirens, attempts were gradually made to focus on a new beginning. Special orders were taken on to prevent the remaining skilled workers being drafted into the regular or territorial army. Five days before the plant was seized by the Red Army, the Chairman of the Supervisory Board urged workers not to neglect the stock production of peace goods.

The previous Christmas, Wintermantel had written to Vielmetter's grandson and designated successor, then in the army:

“Let us hope that in the course of the New Year we shall hear the pipes of peace heralding a good peace. Keep healthy and poised for action, for you will have ample opportunity to apply yourself to great things.”