Competition heats up between road and rail

In a radio address given two days after his appointment as Reich Chancellor, Hitler promised his voters “work and bread”. Indeed, it was the surprising success of state-sponsored employment programs that garnered his regime its greatest support. Though not necessarily politically aligned with National Socialism, many business owners placed great hopes in the “incredible turnaround in economic development,” which the board of Knorr-Bremse AG dated precisely in its annual report: “This turning point was January 30, 1933.”

The company experienced increasing order volumes and was able to resume hiring, after the transportation industry had felt the full force of the economic downturn. The construction of the Reich motorways was the new regime’s most prominently staged employment initiative. It also underscored Hitler’s vision of the automobile as the transportation mode of the future, favored over rail for both civilian and military purposes.

The noticeable economic upturn that marked the beginning of the Third Reich immediately brought a significant shift in Knorr-Bremse’s sales focus. The national railway company Deutsche Reichsbahn, by far its largest customer, was commissioned to build the motorways and took on responsibilities in motor vehicle development. The Reichsbahn began systematically expanding its own motor vehicle fleet, launched bus services, and became one of Germany’s largest commercial vehicle operators. In 1934 alone, the Reichsbahn put 1,000 trucks with Knorr-Bremse compressed air brakes into operation. This helped air brake technology achieve a breakthrough in road transport, and Knorr-Bremse was also able to rapidly expand its position in commercial vehicle braking systems thanks to continuous technical development.

Info

Reference to the content of this page

To mark the company's 100th anniversary in 2005, the history of Knorr-Bremse AG was compiled and published in a special book. The book is entitled "Safety on Rail and Road" and was written by Manfred Pohl. This book also includes a chapter on the history of Knorr-Bremse between 1933 and 1945, the time of the Third Reich (pp. 91 to 114). The content of this page of our website is taken from this chapter; the attached PDF is a scan of the original pages of the book (available in German only).

Knorr-Bremse in the Third Reich

The trend toward faster and heavier vehicles, with payloads of up to 36 metric tons, ultimately secured the widespread adoption of compressed air brakes among other vehicle operators as well. By 1937, Knorr-Bremse was supplying approximately 22,000 braking systems for motorized commercial vehicles and around 11,000 systems for trailers. By this point, roughly 80% of all articulated trucks entering the German market were equipped with Knorr-Bremse air brakes.

Knorr-Bremse also actively expanded its repair business and retrofitting of air brakes during this period. At the end of 1936, it began establishing service centers for brake systems and set up a central spare parts warehouse in Frankfurt am Main. Two years later, there were already 200 authorized workshops in Germany. However, as hydraulic brakes began to gain traction in automobiles, Knorr-Bremse chose not to adopt this development, stating in 1936 that it would not “follow the American lead”. Knorr-Bremse retained its focus on a combined compressed air and hydraulic brake system, incorporating Knorr’s compressed air technology alongside components from hydraulic specialist Alfred Teves (ATE) and Krupp. The only fully hydraulic system adopted at Knorr-Bremse was a hydraulic handbrake for rail vehicles.

During the furious expansion in the commercial vehicle sector from 1933, sales in Unit III (automobile brakes) increased fourteenfold in just four years. By 1937, this unit achieved sales of 11.9 million Reichsmarks (RM), even surpassing Unit I (mainline railways), which suffered under the “Reichsbahn’s continued reluctance to place orders in the rail vehicle sector,” as stated in the annual report published in 1936 for the prior year.

Nevertheless, with assets of RM 23 billion and an annual procurement volume exceeding RM 1 billion, the Reichsbahn remained the “largest company in the world” and an indispensable customer for Knorr-Bremse’s Rail division. Knorr-Bremse had taken early steps to prepare for the new technical challenges facing rail transport due to competition from automobiles and airplanes, a trend apparent since the 1920s. One result was the development of the Hildebrand-Knorr brake, which established a new standard in mainline rail transport just a few years after the introduction of the Kunze-Knorr brake.

Knorr-Bremse also explored other innovations in high-speed rail technology. The company opted for drum brakes over disc brakes as a superior solution for transferring braking force compared to the traditional method of applying force to the wheel tread. The drum brake had already proven successful in Knorr-Bremse’s streetcar applications. The principle of a brake whose effect is independent of the minimal adhesion between wheel and rail was now also made usable for high-speed trains.

In the early 1930s, Knorr-Bremse acquired the company Jores & Müller, incorporating it into Unit II, which now also equipped railcars as well as streetcars and light rail systems. This small specialty company manufactured electromagnetic rail brakes, which work by lowering magnetic shoes onto the rail head, where they are held in place by magnetic force. The electromagnetic rail brake had already been effectively used in streetcar operations. Among the notable projects of Jores & Müller – which retained its name as part of Knorr-Bremse AG until 1944 – was equipping the legendary Rail Zeppelin. Powered by a propeller, the Rail Zeppelin reached a speed of 230 km/h during a test run between Berlin and Hamburg on June 21, 1931. Although the project never advanced beyond the experimental stage due to a number of issues, it exemplified determination of the Reichsbahn to seek its future in higher transport speeds.

As competition with road transport intensified, the Reichsbahn sought to position itself as the truly modern and rapid mode of transport. Freight train speeds increased significantly, and the operating speed on several express train routes was raised at the start of the 1930s.

When the Reichsbahn began operating express railcars, Jores & Müller developed an electromagnetic rail brake for the new train system. This brake was introduced as an auxiliary brake for the Reichsbahn’s express railcars and was first deployed in the legendary “Flying Hamburger” (DRG Class SVT 877). The Flying Hamburger, which used diesel-electric railcars to travel between Berlin and Hamburg at a scheduled top speed of 160 km/h starting May 15, 1933, drew global attention. Featuring advanced braking systems developed by Knorr-Bremse and receiving special attention from the Reichsbahn during its construction, the train was booked out weeks in advance. The Hildebrand-Knorr brake, developed in 1931, was also used in the Flying Hamburger.

Developed at extraordinary speed, Knorr-Bremse’s high-speed train braking systems generated limited revenue, yet they helped the Reichsbahn achieve success on the world stage and confirmed Knorr-Bremse’s role as a development partner to Europe’s largest and most technically demanding rail operator.

In response to the growing mobility demands of metropolitan areas, Knorr-Bremse collaborated with the Reichsbahn to devise new solutions. The Berlin S-Bahn, which was regarded as the most modern urban-suburban railway worldwide, was equipped by Knorr-Bremse with electrically controlled compressed air brakes, motor air pumps, and pneumatic door-closing systems. Through timely reinforcement of its technical staff, Knorr-Bremse introduced several additional innovations in the rail sector over the following years.

Beyond manufacturing compressed air brakes, the company expanded its activities into other product areas during the 1930s. In 1935, Knorr-Bremse formed a syndicate with French and British partners to promote global cooperation in marketing the Isothermos axle bearing, a product the company had been involved with since 1925 in partnership with Walter Peyinghaus’s iron and steel works. Effective January 1, 1938, Knorr-Bremse acquired the firm in Volmarstein, North Rhine-Westphalia, in which it had previously held a silent partnership, renaming it Knorr-Bremse AG, Stahlwerk Volmarstein. With this acquisition, Knorr-Bremse boasted a powerful foundry operation with around 1,000 workers.

Knorr-Bremse sought to open new markets, especially by manufacturing pumps and compressors, which had long been integral components of its compressed air braking systems. A new Unit IV was established to produce, among other things, industrial compressors for well over 100 applications.

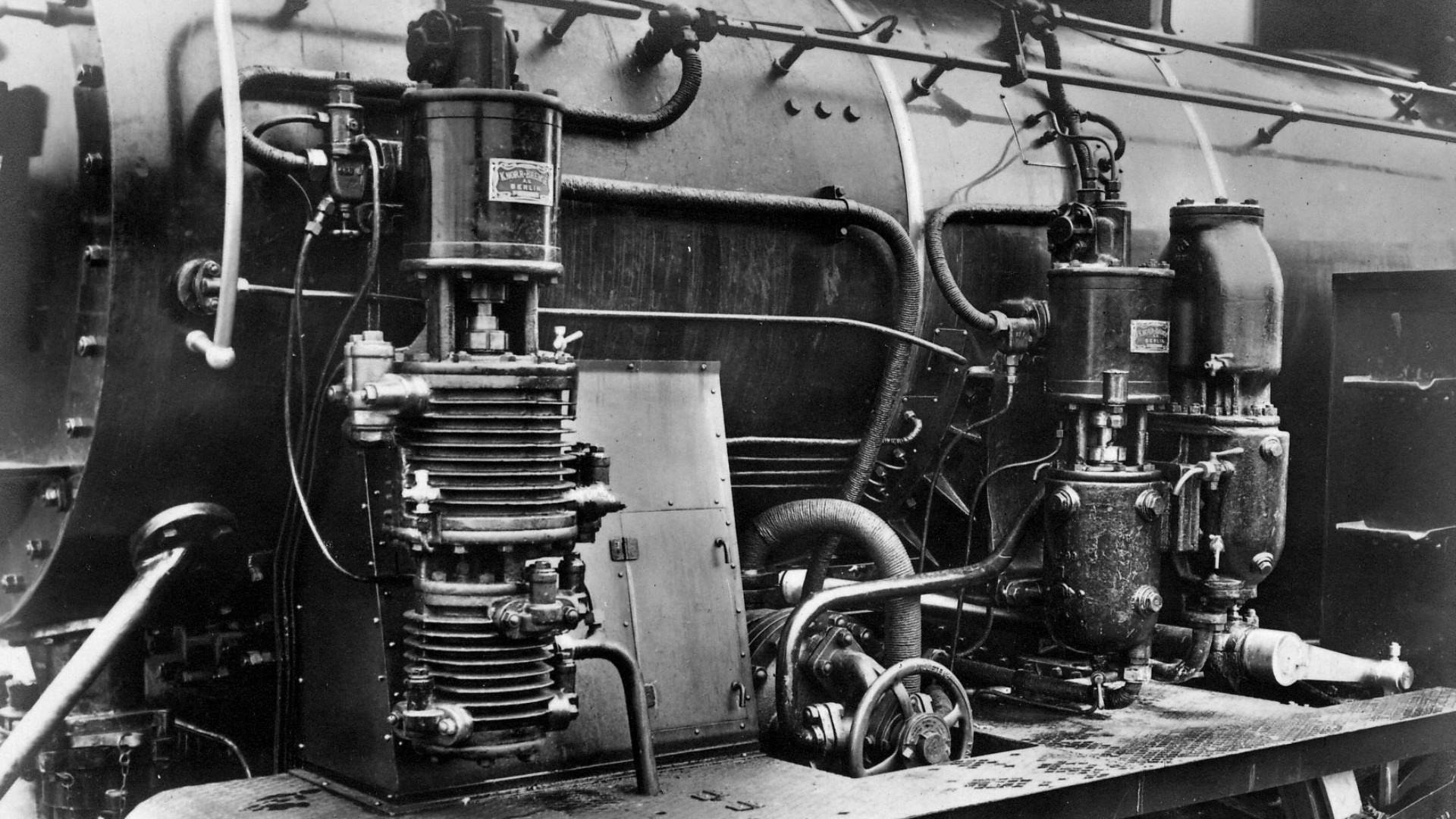

The appointment of engineer Hans Peters, hired by chairman of the executive board Johannes P. Vielmetter in 1926 as a testing supervisor, proved particularly valuable. Knorr-Bremse became Germany’s largest manufacturer of steam air pumps. From the mid-1930s, it also produced high-pressure pumps, which were installed in vehicles such as the whaling mother ship Walter Rau.

Knorr-Bremse systematically expanded its position in compressor production. To boost sales, it added spray guns and demolition hammers to its product line. Efforts were made to secure an English licensee for the latter. The company supplied pneumatic tipping mechanisms for coalfield dump cars, while Unit IV also manufactured clutches and gearboxes under license. By producing signal technology equipment, Knorr-Bremse made its entry into the train control systems segment. Although sales from these new products was modest compared to braking systems, some of them raised high hopes for new sales markets.

One product area, initially generating little revenue, was an armaments unit established in May 1934 under the designation “RB” and kept strictly separate from the rest of the factory. Later referred to as Unit V, it focused on experiments with a patented compressed air-controlled machine gun, which initially resulted in losses for the company.

Between the global market and the “European New Order”

Knorr-Bremse maintained a presence in many countries worldwide, including Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Iran, Yugoslavia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and Hungary. The Kunze-Knorr freight train brake had already been introduced in Germany as well as in Sweden, the Netherlands, Turkey, and partially in Hungary.

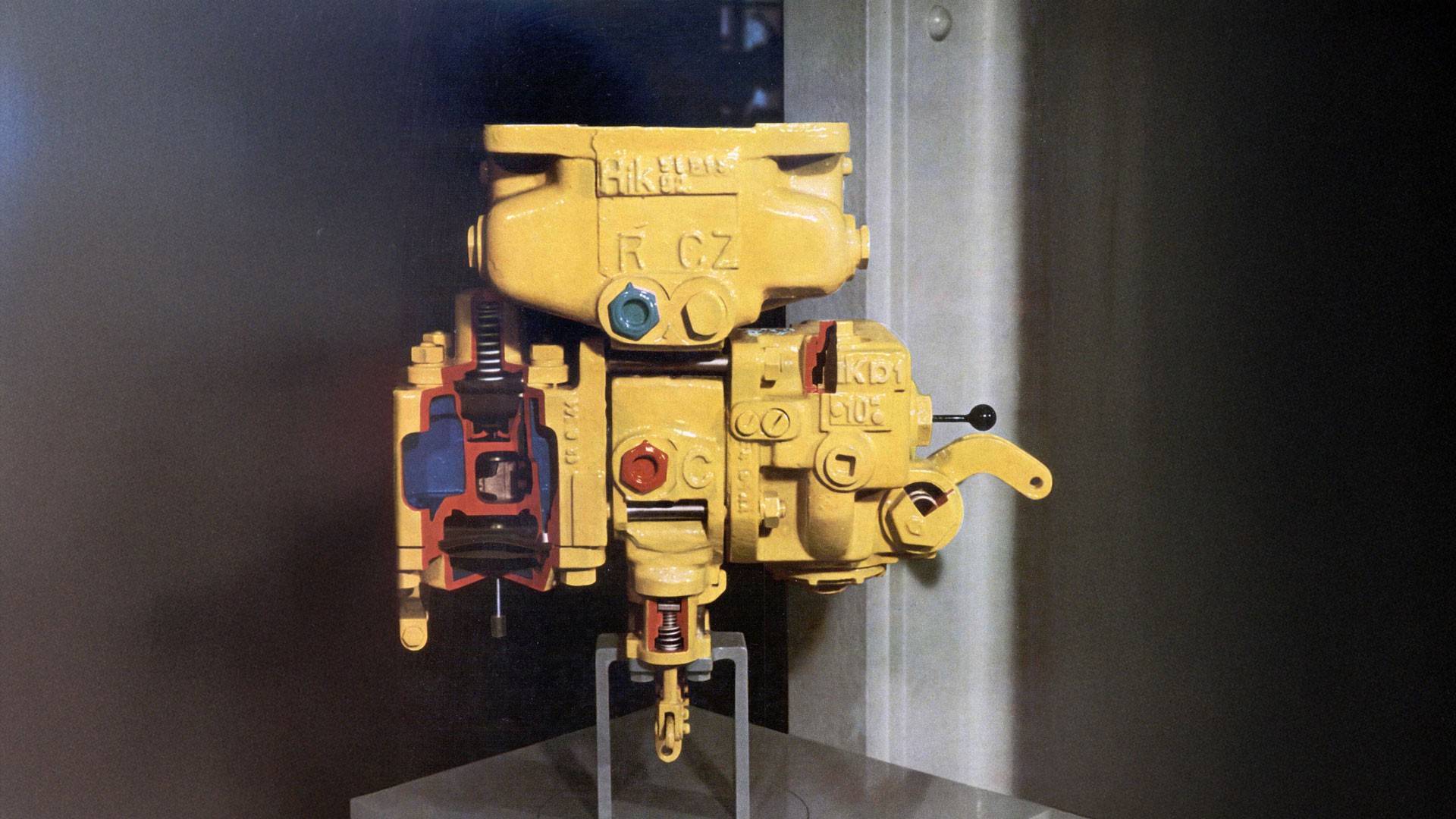

Newly developed systems for high-speed rail travel also quickly gained international interest. For example, starting in 1936, Denmark’s state “Blitz trains” were equipped with Knorr-Bremse’s magnetic rail brakes and external shoe drum brakes. Unit II, which produced systems for streetcars and railcars, supplied to countries including Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Spain, Turkey, and South America. Starting in 1937, 140 railcar sets equipped with brakes from Knorr-Bremse were exported from Hungary to Argentina. However, the main driver of international sales was the Hildebrand-Knorr brake, which the Reichsbahn soon adopted across all new passenger and freight cars.

By 1931, the “Hik” brake had received certification from the International Union of Railways (UIC) for international transport. In 1937, the “Hikss” emergency brake was awarded the Grand Prix in the Safety Systems category at the Paris World’s Fair. Knorr-Bremse engaged in promising negotiations with numerous foreign railway operators and, in direct competition with Westinghouse, sought to establish a foothold in South America. Trials for the Hildebrand-Knorr brake began in Brazil in the spring of 1938 on the Companhia Paulista line between Tapuya and San Carlos, demonstrating its reliability on long, heavy trains.

Like its predecessor, the Hik brake found its first foreign market in Sweden. By 1939, the decision had also been made to introduce it in Norway, Austria, Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria and Iran. There, the Hik brake was installed in British wagons and deployed on the Trans-Iranian Railway, inaugurated in 1938, connecting the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf. Denmark and Hungary also opted for the Hik system. In countries with domestic railway industries, authorities insisted on local manufacturing. However, a lack of funds due to inflation and the global economic crisis, and above all the strict foreign exchange controls introduced after the banking crisis of 1931, made it difficult for German companies to set up their own production facilities abroad.

At least in Hungary, Knorr-Bremse sought to acquire a majority shareholding in Telefonfabrik AG, Budapest, with which it had a licensing agreement since 1926, but this effort failed in 1933 due to currency transfer issues. In Romania, an initial attempt to establish Frana Knorr evolved into a 1936 licensing agreement with the N. Malaxa locomotive factory in Bucharest. That same year, a licensing agreement was signed with Gebrüder Hardy AG in Vienna to produce the Hik brake and other Knorr products for Austria. In Norway, Knorr-Bremse granted Kongsberg Vaabenfabrik manufacturing rights in 1936, with high-quality components such as control valves and brake cylinders supplied from Berlin initially. In Sweden, Knorr-Bremse had a long-standing partnership with Nordiska Armatur Aktiebolaget, established in 1919 with factories in Stockholm and Lund. This culminated in a 1937 agreement for the production of the Hik brake for the Swedish market.

Shortly afterwards, however, the Third Reich’s policy of conquest and extraction meant that the spread of the Hik brake was shaped by the “European New Order” under German control. Due to the war, major orders for Turkey and Iran were lost, as well as for Estonia and Latvia, countries that fell within the sphere of influence of the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. Efforts to gain a foothold in South America also had to be discontinued with the outbreak of war. Relations were now focused on the railroad administrations and licensees of Knorr-Bremse in occupied or neutral European states surrounded by German forces.

In Sweden, cooperation with Nordiska Armatur Aktiebolaget (NAF), whose plant in Lund with several hundred employees produced braking equipment for the Swedish State Railways under a license agreement with Knorr-Bremse, remained comparatively straightforward. Not that the company, in which Johannes P. Vielmetter held a personal stake of about 8%, was an easy partner. Lengthy disputes over the distribution rights tied to the licenses were only resolved in 1936. The new licensing agreement with Knorr-Bremse, signed in 1937, was reaffirmed by NAF in the spring of 1940. In neutral Sweden, the Berlin-based company enjoyed a good reputation throughout the war, which aided ongoing collaboration with the licensee. In 1941, Knorr-Bremse granted the Thulin Works in Landskrona, Sweden, the right to manufacture and distribute braking equipment for road vehicles, making it the first foreign company to receive such authorization.

The annexation of territories by the Third Reich, followed by the military conquest of large parts of Europe, also paved the way for German companies and products to enter the occupied and annexed countries. Following the Anschluß with Austria (its forced annexation) in March 1938, and after “consultations” with German authorities, a decision was made to adapt Austrian railway vehicles to German technology as quickly as possible. Despite its licensing agreement with Knorr-Bremse, Gebrüder Hardy AG in Vienna had been working on the development of a new control valve that used innovative rubber seals instead of the metallic seals found in the Hik valve. However, this development was abandoned after the political events of 1938. William Francis Hardy, the British-born head of the company, left Austria and served in the Allied navy during the war. The company was placed under government-appointed administration by the new regime. Only then did it begin manufacturing the Hik brake for the Austrian state railway, now integrated into the Reichsbahn, under the terms of the two-year-old license agreement. Similarly, the state railways of the Netherlands and Denmark only began systematically adopting the new braking system under German occupation.

After Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, the view to the east was also engulfed in the maelstrom of military violence. In August 1941, the Knorr-Bremse executive board anticipated entirely new challenges: “The European New Order will likely bring new demands in the area of freight train brakes. Longer continuous routes will result in significantly greater train lengths and weights, especially if Russia should one day be included in the European transport network.”

The regime’s strategy included exerting pressure on industry in occupied countries while avoiding interference in private competitive markets.

Knorr-Bremse’s executive board therefore considered it a significant achievement to secure, in October 1941, a licensing agreement for the Škoda Works in Prague to produce brakes at its Adamsthal branch. Until then, Škoda had promoted the competing Božič brake. The board noted: “We see this agreement as another major step towards the exclusive use of the Hildebrand-Knorr brake in Europe.” Shortly before this, the Reichsbahn central office had approved Škoda’s plan to produce all brake components for Reichsbahn locomotives not protected by Knorr-Bremse patents at the Adamsthal plant. The Third Reich strove to bring the economy in (partially) annexed territories under German control through pseudo-legal means. Among its targets were Gebrüder Hardy AG in Austria, a territory now known as the Ostmark (Eastern March), and Škoda in Prague, now capital of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

By then, much of Europe was directly served by the Deutsche Reichsbahn. The “Ostbahn” railways operating in the General Government (occupied Poland) placed increasing orders with Knorr-Bremse. The Knorr plant in Berlin also supplied railway industries in occupied Belgium and France, which were compelled to produce exclusively for the Reichsbahn. Even the Westinghouse plant in Paris now delivered equipment based on Knorr-Bremse designs, reversing the pattern from a decade earlier, when Knorr-Bremse had supplied brakes based on Westinghouse designs to French railways.

There is no evidence to suggest that Knorr-Bremse AG ever attempted or even had the opportunity to use political pressure to obtain orders or license agreements. In fact, the executive board had increasing reservations about the surge in foreign orders, often delaying acceptance to avoid excessive delivery delays. Unlike many other German companies and investors, Knorr-Bremse did not seek to acquire potential suppliers in occupied countries, despite having to subcontract foreign firms due to rising order volumes, a move that carried the risk of creating future competitors. During the war, at least 57 subcontracting orders were issued to companies in occupied territories, including 21 in France, 27 in Belgium, three each in Italy and Denmark, one in Norway, and two in the General Government (occupied Poland).

In summer 1943, as Allied air raids intensified, the Reich Ministry of Armaments and Munitions ordered Knorr-Bremse to relocate parts of its operations to sites further east. The company assumed control of facilities in Myszków and Sosnowiec, in Upper Silesia – territories that had been Polish since 1920 but were reincorporated into the Reich after the German occupation. These facilities, previously a sheet metal and enamelware factory and a large textile factory, had been placed under the Main Trustee Office East (HTO) after the German invasion. Knorr-Bremse turned down the opportunity to purchase the properties and instead signed lease agreements with the HTO. The two auxiliary plants employed around 1,000 and 1,200 workers, primarily Poles, with some Berlin employees relocated there to produce items essential for the war effort, including supplies for the Luftwaffe.

The supervisory board was informed of “very serious pressure” from relevant committees within the Armaments Ministry if designated delivery programs were not precisely met. The executive board found itself increasingly constrained in its decision-making and faced with growing difficulties in supplying the German railway administrations, which now extended well beyond the Reich’s borders, with all the requested equipment. Orders from the Ostbahn rose to RM 800,000 in 1942. These orders not only enabled the war-related operations of the “railways essential for the military effort and the troops,” as the Knorr-Bremse management stated in its annual report. The development of an efficient railway system in occupied Poland was also a prerequisite for the seamless “evacuation” of the Jewish population of half of Europe to the extermination factories of the Third Reich.

One can only speculate as to what the management in Berlin knew, did not know, or chose to ignore about the broader implications of their work. The Knorr-Bremse auxiliary plant in Sosnowiec, which began production in February 1944 and employed about 300 Berlin staff members until the end of the war, was located less than 20 kilometers from the Auschwitz extermination camp. The Nazi regime kept the machinery of murder hermetically sealed off from the outside world. What little information did leak out was so unimaginable that it was scarcely believed, either within the Reich or abroad, until Allied troops reached the camps and liberated the few survivors. In any case, whatever might have been known did not make its way into the preserved records of Knorr-Bremse.

Knorr-Bremse in the Armament and War Economy of the Third Reich

Under the law of February 10, 1937, the Reichsbahn was placed under the direct authority of the Reich and thus the control of the Nazi regime, and was officially renamed “Deutsche Reichsbahn.” The new Reichsbahn Act of July 4, 1939, explicitly subordinated the railway company to the “needs of national defense.” However, the expansion of operational resources lagged far behind the Reich’s immediate rearmament efforts. The conviction expressed by chairman of the executive board Johannes R. Vielmetter shortly after the outbreak of war that “building railway cars is just as important for the war as producing any kind of weapon” was soon confirmed. It was also shared by the Army Administration, which was tasked with setting production quotas and allocating raw materials to the industry.

In 1940, an average of 4,000 Hik-type freight and passenger train brakes were delivered each month from Berlin production to the Reichsbahn and abroad. Beginning in early 1941, the Munich subsidiary, Süddeutsche Bremsen AG (Südbremse), also supplied the Reichsbahn with 1,500 Hik control valves per month, increasing production to more than 2,000 valves monthly by the end of the war.

In 1942, production management was placed directly under Albert Speer, the newly appointed Reich Minister for Armaments and Munitions, who established a Main Committee for Rail Vehicles for this purpose. Consequently, Knorr-Bremse was required to increase production by approximately 80%, primarily in locomotive equipment. Together with relocated factories in Myszków and Sosnowiec and the Munich subsidiary, Knorr-Bremse supplied 500 complete locomotive brake systems per month in the final war years, alongside approximately 250 Hik brakes per day, mainly for freight cars. Overall, the sales of Division I (responsible for mainline railways) increased sixfold between 1937 and 1943, from RM 11.8 million to RM 72.6 million. In Division III, focused on automotive brakes, the decline in civilian orders at the start of the war was offset by increased orders for military stock expansion. However, sales of commercial vehicle brakes, which had grown extraordinarily before the war, were increasingly subject to raw material restrictions for the motor vehicle industry and, after peaking in 1941, fell back to RM 18.7 million.

The armaments unit also gained significance during the war as Knorr-Bremse produced large quantities of pumps for aircraft and the navy, as well as gun barrels for anti-tank weapons and shells for the army. The armaments unit employed around 400 people during the war. Knorr-Bremse was also involved in a number of military development projects. Toward the end of the war, two employees at the Peenemünde rocket center worked on designing air-pressure-damped brake sleds for launching the so-called “V1” retaliation weapon, though these were never used. Despite these activities, the share of the armaments unit in total sales averaged only around 6% in the war years, peaking at 13.3% in 1942. Throughout the war, Knorr-Bremse remained primarily occupied with the production of air brakes for vehicles, above all rail vehicles. This was highlighted by the newspaper Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung on June 27, 1935: “Knorr-Bremse grew up as a brake company, and this branch of production will always remain the backbone of its industrial activities.”

The situation was different for subsidiaries. Südbremse in Munich recovered only slowly after ending its railway brake manufacturing program in 1934, which had briefly resumed for a reparations delivery to Belgium. Its outdated engine program provided little work. A turning point came in early 1937 when, through Johannes P. Vielmetter’s mediation, the firm secured contracts from the Army Ordnance Office to produce detonators and shells. In 1938, it began manufacturing aircraft engine components for the Reich Air Ministry. Engine production, which was laboriously expanded at the same time, was also converted to army deliveries at the beginning of the war.

In Munich, direct armaments production was conceived from the outset as a stopgap that was not to be given more prominence than necessary. When Südbremse began producing Hik control valves in 1941 to ease the burden on its parent company, Knorr-Bremse’s executive board took a renewed interest in the production situation at its Munich subsidiary, and the latter felt compelled to justify its continued arms manufacturing. The Südbremse board argued that pre-war armaments production had restored the plant’s viability. While aware of the disadvantages of its diversified production for the army, navy, air force, agriculture, and railways, the management asserted in July 1941 that “perhaps today and in the near future, the advantages of not being tied to one sector outweigh the disadvantages.”

In Mannheim, the Südbremse-affiliated Motoren-Werke benefited from army demand, while peace-time contracts were withdrawn at the outbreak of war. The plant’s expansion, begun in 1938, was repeatedly extended, and the workforce grew to over 2,000 shortly after the war began. Still, the Mannheim plant was working at full capacity with the construction of engines.

The armament boom also significantly influenced Carl Hasse & Wrede GmbH, in which Knorr-Bremse now held a 75% stake. As early as the 1930s, the management saw global rearmament as an opportunity to supply customers with complete, specialized machinery. In 1930, under strict secrecy, the Army Ordnance Office had commissioned Carl Hasse & Wrede to develop a shell-turning lathe for artillery shell production using tools for hard-metal processing. From the mid-1930s, substantial orders were secured across Europe and South America, mainly from state-owned enterprises. In 1935, the company established its own offices in Shanghai and Tokyo.

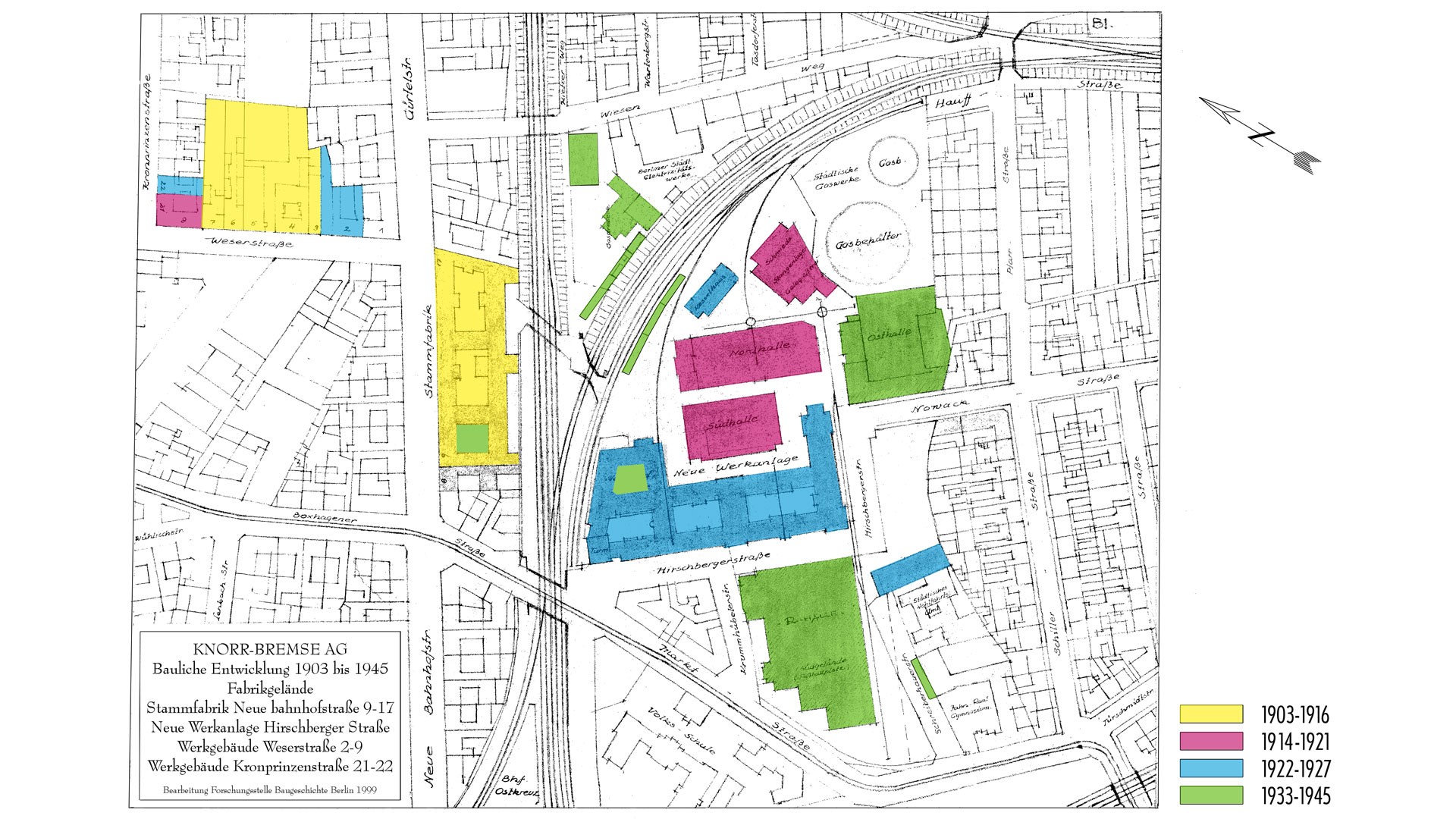

Given the scarcity of foreign currency, export activities were welcomed by the Reich authorities. In 1937, Carl Hasse & Wrede received approval to establish a demonstration facility equipped with machines for manufacturing shells and fuses, which could also be showcased to foreign clients. The company acquired the site of a former iron foundry in Berlin-Britz from Knorr-Bremse, where, after extensive renovations, the demonstration facility was inaugurated in 1938 as Plant IV. By this time, Carl Hasse & Wrede’s workforce had increased tenfold compared to 1933, exceeding 4,000 employees. A significant portion of the machinery was still being exported, particularly to the Soviet Union. Annual sales saw a steep rise from a low of just under RM 1.3 million in 1932 to RM 23.6 million in 1938.

Carl Hasse & Wrede decided to consolidate its production at an extensive new site. On November 25, 1938, the management approached the office of Albert Speer, the General Building Inspector for the Reich Capital and later Minister of Armaments, and was allocated a building site in the area designated “Industrial Zone 15 of the General Building Inspectorate” near Marzahn, northeast of Berlin’s city center. The new facility was quickly constructed under the direct supervision of the General Building Inspectorate, utilizing the framework of a structure initially intended for the Reichsbahn.

One day before the topping-out ceremony on August 31, 1940, the managing directors of Carl Hasse & Wrede, Paul Peter and Wolfgang Anger, signed a classified contract with the German Reich, represented by the Army High Command (OKH). Under this agreement, the company committed to primarily using the new facility to fulfil delivery orders placed directly or indirectly by the OKH. In return, the Reich contributed a subsidy of RM 4.9 million toward construction costs. Simultaneously, the share capital of Carl Hasse & Wrede was increased by RM 4 million to RM 5 million, with Knorr-Bremse’s stake rising to 90%. The relocation was completed by March 1942. In addition to the vast new plant, the subsidiary in Britz continued operations.

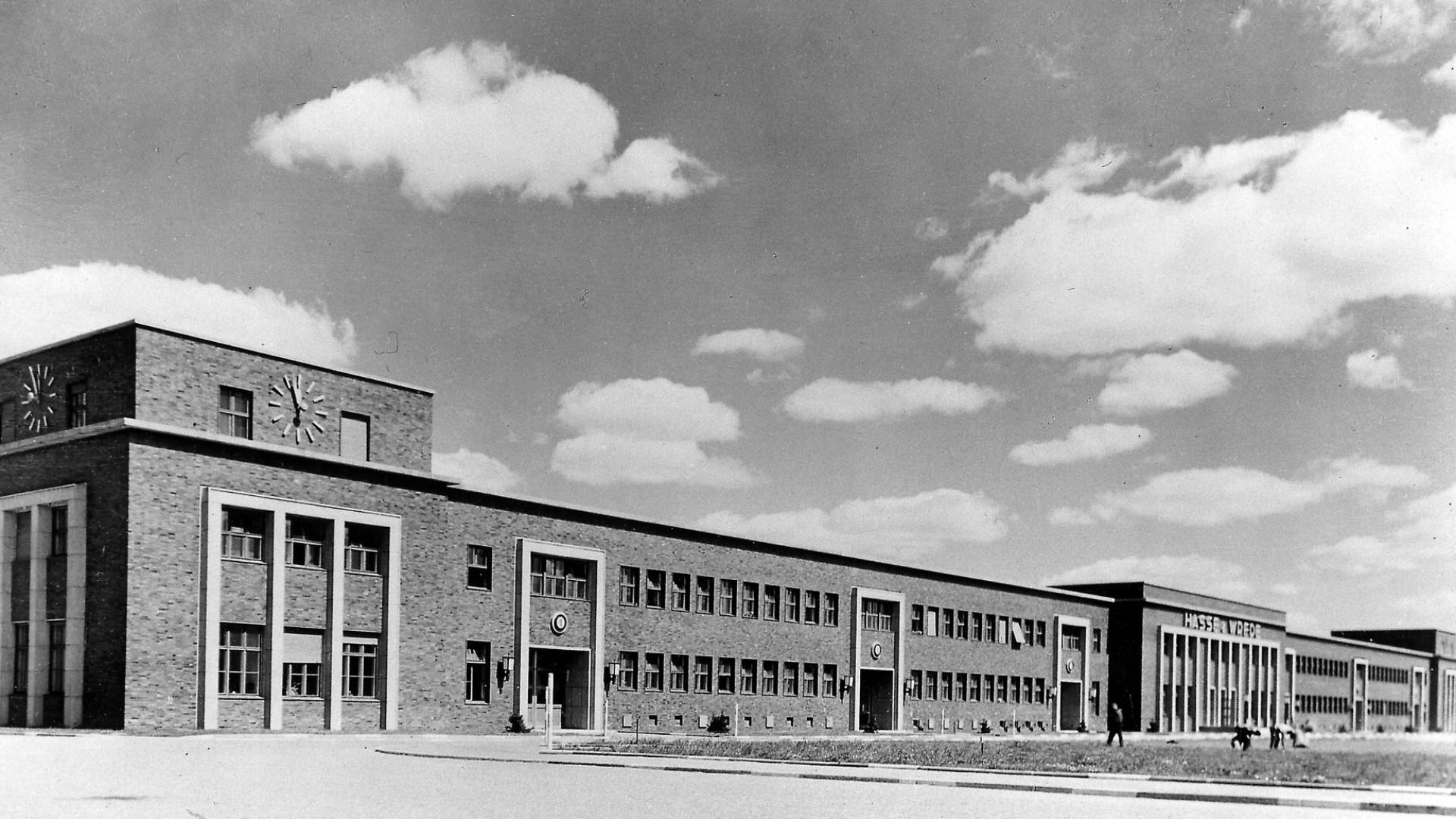

The Hasse & Wrede management specifically requested an architect from the General Building Inspectorate to design the large industrial facility. The exterior of the concrete building, clad in red brick, clearly reflected the modernist aesthetic of the 1920s and 1930s. Behind the brick façade was a factory hall measuring 200 by 200 meters. More than 4,000 employees worked on 1,400 state-of-the-art processing machines across a continuous area of 40,000 m².

This massive expansion, driven by the demands of the armaments industry, required significant investments. The new Carl Hasse & Wrede plant in Marzahn ultimately cost RM 24.5 million, financed primarily through loans. The company, whose senior manager Julius Wrede had died on February 23, 1939, recognized internally that it had entered into dependencies that were “not without risk,” adding: “Hasse & Wrede, through the expansion of the plant, has become the largest machine tool factory in Europe, perhaps even the world.

This indicates that the growth of Hasse & Wrede, instigated by the OKH, exceeds the typical capacities of machine tool factories. Utilizing this capacity after the war will be a serious challenge.” The facility was therefore described as a “shadow operation of the armaments industry.”

By the end of 1939, Knorr-Bremse and its subsidiaries employed over 20,000 people. The armaments-driven economic boom had led to extraordinary expansion, particularly in the subsidiaries. However, the inherent risks of this politically dependent growth were well understood. Hence the management of Knorr-Bremse sought to avoid building up excessive capacities within the company itself. Johannes P. Vielmetter informed the supervisory board in the summer of 1938: “We are reluctant to undertake structural enlargements and instead intend to enlist the cooperation of affiliated plants.” This strategy also remained in place during the war. Once Südbremse’s capacities were fully utilized, the demands of the war economy were increasingly perceived as a burden. Significant delivery backlogs carried the risk that contracts could be awarded to competitors, who would then gain access to technical drawings and vital know-how.

The relationship with the primary customer, the Reichsbahn, brought additional strains. Traditionally, deliveries to the Reichsbahn were billed using a “cost-plus” model, where the company could add a certain profit margin to submitted and verified cost calculations. These prices, often well above production costs, also covered substantial development expenses. However, cost-plus was abandoned during the war in favor of a rigid fixed-price model. Starting in 1940, the Reichsbahn significantly reduced prices on several occasions. Johannes P. Vielmetter complained to the Reichsbahn Central Office in Berlin on June 22, 1940, that his company had been “reduced to the status of a screw factory.”

Despite declining or entirely absent profits, Knorr-Bremse consistently sought to fulfill its delivery commitments until the war’s end. This persistence was not solely due to the immense pressure exerted by armaments committees. The company was also mindful of the post-war situation. “It is essential,” the executive board stated in March 1943, “that our company retains control of this production, as otherwise, there is a risk that competitors could emerge who would not only satisfy the extraordinarily increased demand during the war but also compete with us at home and abroad in the coming years.” As a result, no distinction was made between wartime demands and the company’s long-term interests.

The unwavering commitment to fulfilling wartime obligations also posed significant challenges in internal operations, especially regarding personnel. As the board reported in early 1943:

“A failure would have enormous repercussions for the war effort and for our company. The greater output required places exceptional demands on internal organizational structures, as skilled personnel are lacking, and the gaps caused by military conscription can often not be adequately filled.”

From full employment to forced labor

For the Knorr-Bremse workforce, the economic upswing since 1933 had translated into a noticeable improvement in wages and additional benefits. Even before the war began, with nearly 5,000 employees, staff shortages occurred. Now there was full employment, and the lack of workers, particularly skilled labor, was acutely felt. The management sought to address this through retraining programs, mechanization, and streamlining of administrative tasks. For some time, Knorr-Bremse had also been stepping up recruitment of female employees. The number of female workers quadrupled between 1933 and 1938, rising from 149 to 621, while the total workforce more than doubled from 2,152 to 4,925 in the same period.

During the war, as military conscriptions increased and industrial demands grew, the need for additional labor escalated. By the war’s end, more than two-thirds of the male German workforce at Knorr-Bremse’s main Berlin plant had been conscripted or killed. The ability to fill these positions with female workers or untrained personnel quickly reached its limits. Workers faced increasing restrictions: from the summer of 1941, repeated unexcused absences no longer resulted in dismissal but instead carried the threat of imprisonment for up to three months. Nevertheless, the outflow of personnel threatened to interrupt production.

To sustain manufacturing output during the war, the Nazi regime ruthlessly exploited the labor force of occupied territories. Many people volunteered for work out of sheer necessity. However, their numbers were far from sufficient, and increasingly people were brutally deported from their homeland to perform forced labor in German factories. Prisoners of war were also compelled to work, a practice that, while technically allowed under international law, often took place under appalling conditions. By August 1944, a total of 7,615,970 foreign laborers were registered within the territory of the Greater German Reich.

For businesses, employing foreign laborers often entailed additional costs. Companies were required to provide food and accommodation. Knorr-Bremse AG and its subsidiaries also employed large numbers of foreign workers. In a supervisory board meeting on March 4, 1943, the management reported:

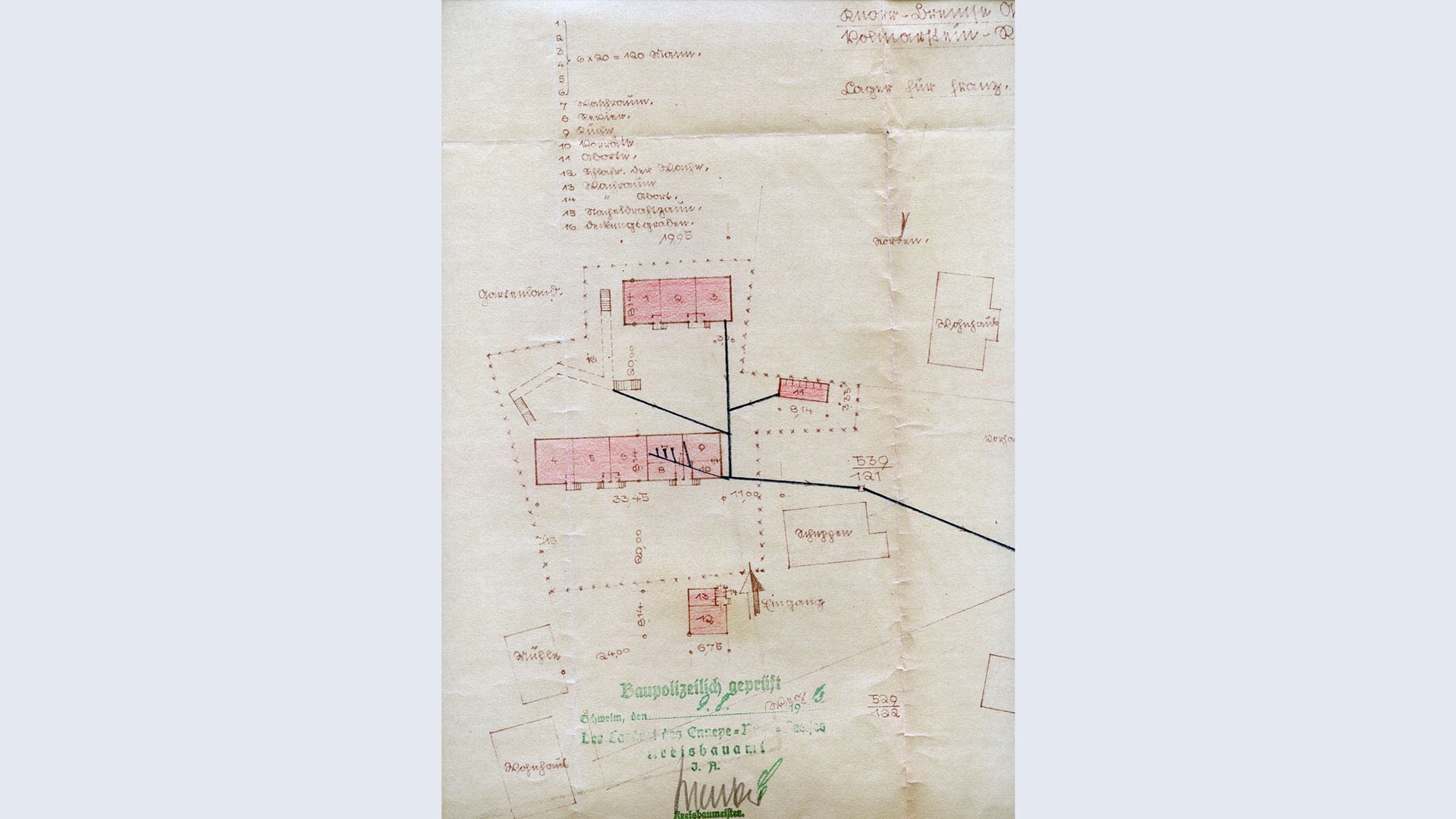

“The increased use of foreign workers, primarily Eastern European and French nationals, meant that we had to set up barrack camps, and their construction was subject to certain regulations. We built some of these camps ourselves, while others were constructed by the Reich and leased to us for use. [...] Approximately 2,700 foreign workers have been housed in these barrack camps.”

That same month, the number of foreign workers at Knorr-Bremse’s main Berlin plant reached its wartime peak at 3,101, representing 42.3% of the total workforce of 7,334. Among the industrial occupations, the ratio of foreign workers was even higher, at 48.7%. In the branch plants located in the General Government territory, the workforce was predominantly Polish. Including these workers, the number of non-German employees reached a peak of 4,090 in July 1944, when Knorr-Bremse employed a total of 8,269 people across Berlin, Myszków, and Sosnowiec. At Südbremse, foreign workers made up as much as 50% of the over 2,000 employees, including French and Soviet prisoners of war. In some manufacturing departments, foreign workers accounted for up to 75% of the workforce. As early as 1940, 100 prisoners of war were working at the Volmarstein steelworks. By September 1944, the number of foreign workers there rose to 344, plus an additional 273 prisoners of war, out of a total workforce of 1,285.

These numbers reveal little about the working and living conditions of foreign workers, which varied greatly depending on their origin. A report from July 11, 1942, listed foreign workers from 19 different countries at Knorr-Bremse’s main plant in Berlin. They included so-called Eastern workers (Ostarbeiter) from the Soviet Union, as well as Belgians, Czechs, Italians, French, Yugoslavs, Croatians, Dutch and Poles. There were significant numbers of women, especially among the Eastern workers. Prisoners of war were also employed. Western Europeans often had relatively more freedom and were treated better than Eastern workers, who faced particularly harsh restrictions.

In a circular from June 1942, the Knorr-Bremse management claimed that Eastern workers “voluntarily offered their labor.” However, the statement was accompanied by a warning to German employees: “As nationals of an enemy power, they are granted no freedom of movement. Keep them under strict control to prevent escapes.”

All company employees were required to wear color-coded badges on their clothing for identification: supervisors wore white badges, German employees blue, foreigners red, and Eastern workers green. Foreign workers were also housed in separate barrack camps according to their nationality. The female Eastern workers were escorted daily under guard from their camp to the factory. Similarly, Knorr-Bremse subsidiaries maintained their own camps on company premises. Foreign workers were most likely to work in closed groups. Their interaction with the German workforce was limited and typically mediated by designated supervisors tasked with training and overseeing them. The female Eastern workers were trained to operate lathes. Conduct towards foreign workers ranged from the sometimes extremely rude behavior of supervisors to cases of German employees offering individual assistance.

Initially, the company’s subsidiaries sought to draw upon all available reserves from the increasingly regulated labor market. For example, the management of Südbremse requested more female German workers, but municipal labor offices were unable to meet the demand. In May 1943, the management reported to the supervisory board: “The labor shortage was more or less remedied by recruiting foreigners of all nationalities and additional prisoners, but skilled workers remained unavailable.”

From 1943, Knorr-Bremse’s accounting calculated a decline in sales not only per worker but also per wage unit, which it attributed to the employment of foreigners, despite their wages being lower than German workers, as stipulated precisely in the regulations. Carl Hasse & Wrede reported a decline in total sales in 1942 due to the major outflow of skilled workers and the resulting shift to foreign labor.

The companies did not insist on recruiting foreign workers but they did view it as necessary, thereby participating in a system built on the ruthless exploitation of these individuals. The extent to which the inhumane tyranny of the Third Reich had permeated the apparent normality of everyday working life is starkly illustrated in a report from the Knorr-Bremse management to the supervisory board regarding employment at the Volmarstein steelworks:

“On average in 1942, 30 industrial apprentices were employed, compared to 32 in the previous year. At the end of March of the business year, 120 Soviet prisoners of war arrived, of whom only 75 were still working by the end of the business year. The Soviet prisoners of war were in very poor health: many had to stop working after a matter of weeks or months due to death or illness.”

Dangers and failures

The vague anti-capitalist sentiment within the National Socialist ideology and movement quickly gave way to pragmatic action focused on economic stability after Hitler’s “seizure of power”. However, the racist ideology of the new regime, which aimed to oust Jews from German economic and social life, had an immediate impact. One of Berlin’s most respected Jewish entrepreneurs, Isidor Loewe, had been involved in the founding of Knorr-Bremse, and until 1932, a member of his family had served on the supervisory board. By the time Hitler came to power, however, there were only a few Jewish employees in prominent positions within the Knorr-Bremse organization.

On October 21, 1935, Käthe Jacobi, a long-time employee of Carl Hasse & Wrede who had most recently been responsible for the company’s entire cash management, was informed that, as a Jew, she could no longer remain employed by the company. In February 1937, Wilhelm Strauß, a Jewish board member of Südbremse in Munich, also left his position. It is no longer possible to determine the extent to which political pressure played a role in his decision. According to a later account, Vielmetter’s separation from Strauß was a reaction to a demand from the headquarters of the Nazi-controlled German Labor Front. However, there is no evidence of antisemitic attitudes on the part of the company management.

Both Käthe Jacobi, who personally appealed to Johannes P. Vielmetter after her dismissal, and Wilhelm Strauß subsequently received financial support from their former employer. Herbert Waldschmidt, who joined the Südbremse board alongside Strauß in 1934, continued to employ a “non-Aryan” secretary and was thus able to protect her from persecution until shortly before the end of the war. Like Strauß, who had emigrated to safety, she returned to work for the company after the war. Julius Wrede’s son-in-law and former managing director Günther Beling, who was classified as a “half-Jew” under the Nazi regime, was even elected to the supervisory board of Carl Hasse & Wrede on May 2, 1933, replacing the deceased Walter Waldschmidt. He remained on the board for the remainder of the Third Reich.

However, political pressure was not only exerted on the companies externally. Knorr-Bremse was one of the first large companies where, as early as 1927/28, Nazi “factory cells” emerged among the workforce. After Hitler’s regime took power, the company’s organizational structure was also aligned with Nazi policies. The German Labor Front replaced the previous trade unions, the elected works council was supplanted by a “council of trust”, and the appointment of state “trustees of labor” ended collective bargaining autonomy.

The Law for the Regulation of National Labor of January 20, 1934, also required a new corporate code for Knorr-Bremse AG, under which Johannes P. Vielmetter assumed the function of “works leader” (Betriebsführer) over the workforce of “followers” (Gefolgschaft). However, the German Labor Front’s attempt to embed the National Socialist Führer principle in the company’s operations only had a superficial effect. Nevertheless, the new organization opened avenues for political attack by a horde of informants and careerists.

On September 10, 1937, Johannes P. Vielmetter applied for membership in the Nazi Party (NSDAP). Yet his decision can hardly be interpreted as a political alignment with Hitler’s party, which was well aware of individuals who did not fully conform to its expectations of a “model attitude”. The membership application of technical director Wilhelm Hildebrand on December 8, 1939, was rejected. So was the application of Reinhard Burkhardt, procurator and head of the foreign department, on June 3, 1941, as the party tribunal held his previously expressed distance from the NSDAP against him. In Munich, Herbert Waldschmidt joined the party in 1937. Similarly, Wilhelm Holzhäuser, who succeeded Wilhelm Strauß on the board of Südbremse, applied for membership. However, his earlier affiliation with a Freemason lodge meant his application was only approved five years later through a “pardon decree.”

Finally, the issue of generational succession in the leadership of Knorr-Bremse also entered political waters. Since its foundation, the company had always retained the traits of a family business. It was converted into a public limited company in 1911, and the binding of the shares in a syndicate was intended to facilitate an IPO, an option intended to accompany planned expansions. Yet this plan never came to fruition. The turbulent developments of the 1920s turned Knorr-Bremse into a privately-owned company. By 1941, when Wilhelm Hildebrand terminated the syndicate agreement, Vielmetter was the free majority shareholder of Knorr-Bremse with 87.3% of the share capital.

The company was now facing a different kind of crisis compared to the economic crisis it had weathered a decade earlier. The increased demands on production were difficult to meet and required significant funding. Borrowing from Deutsche Bank had reached nearly RM 11 million by the start of the war, a matter of concern for its board. In this situation, some companies sought alliances with strong or seemingly strong partners. Gesfürel, for instance, having already joined forces with Ludw. Loewe & Co. AG, finalized its merger with the larger entity AEG on February 19, 1942. As part of the transaction, Vielmetter joined AEG’s supervisory board. However, he did not consider such a step for Knorr-Bremse and showed no intention of placing company leadership, which he had exerted almost exclusively since 1907, into new hands. The supervisory board had been discussing the issue of management succession for some time. At the start of the war, Johannes P. Vielmetter was 79 years old, and Wilhelm Hildebrand was 70. The technical director looked back on 40 years of work in the development of the railroad air brake. He had even played a key role in the development of the Kunze-Knorr brake.

In 1937, under clear political pressure, Vielmetter expanded the board for the first time with the appointment of Oskar Maretzky. He had already been associated with Knorr-Bremse as mayor of Berlin’s Lichtenberg district since 1912. Dismissed from office in 1920 for his support of the Kapp Putsch, an attempt to overthrow the Weimar Republic, Maretzky had sided with the Nazi regime after it came to power and was appointed acting lord mayor of Berlin. He carried out his duties as a competent administrative figurehead of the regime without any real political influence.

When the independent municipal administration was abolished in 1937, he had to give up his office and joined Knorr-Bremse, where he was appointed to the executive board at the beginning of 1938. The former mayor enjoyed Vielmetter’s trust and also represented the company in negotiations with the Reichsbahn. However, he turned out to be a poor choice, as he not only failed to shield the company politically, but actively conspired against its leadership. By his own account, he persuaded the “labor trustee” in 1940 to pressure Vielmetter to relinquish his position as works leader.

Meanwhile, the company’s “council of trust” also went on the offensive. On November 7, 1940, it demanded that Vielmetter remove the head of personnel and other politically disfavored employees who were unwilling to perform their duties “in the National Socialist interest.” On December 16, 1940, Vielmetter stepped down from his role as works leader. The difficult position was taken up by Hellmuth Goerz, former managing director of the Volmarstein steelworks, who thus joined the executive board of Knorr-Bremse. Maretzky left the company again in January 1941 “by mutual amicable agreement.”

By this time, political coercion had significantly increased, while the strain on the company from the wartime economy continued to grow. It became increasingly evident that the company was lacking a truly solid leadership. On February 28, 1943, Wilhelm Hildebrand left the executive board. He passed away shortly thereafter, on December 24, 1943, at the age of 74.

After his departure, the board was expanded to include three new members. One of them was Friedrich Hildebrand, son of Wilhelm Hildebrand and a former technical assistant to the executive board. Another was Kurt Anhalt, who had been with the company for nearly 20 years and had established Unit III for automotive brakes. He was married to the widow of Johannes P. Vielmetter’s late son. The third new board member, Alfred Woeltjen, had only joined Knorr-Bremse in November 1942 in a technical leadership role. Since 1934, the engineer had worked in the Technical Office of the Ministry of Aviation under Hermann Göring.

Under political pressure, Johannes P. Vielmetter himself finally resigned from the Knorr-Bremse management in 1943, after initially taking on the newly created position of chairman of the (expanded) executive board. Oskar Maretzky once again acted against him, denouncing him to the head of the Main Committee for Rail Vehicles under the Minister for Armaments and Munitions, Gerhard Degenkolb, for alleged age-related weakness in leadership.

The new works leader Hellmuth Goerz was a member of the sub-committees responsible for brakes in the organization set up in 1942 to control production. However, these roles did not confer political influence. They apparently did not even ensure the usual level of participation in determining technical equipment standards. The primary goal of engaging with the committees’ work was to “avoid having our deliveries controlled by outsiders.” Not without reason, Degenkolb was praised by his minister, Albert Speer, as the “absolute dictator” of rail vehicle construction. An investigation initiated by Degenkolb had concluded that Knorr-Bremse’s production output lagged behind that of comparable plants. Maretzky’s denunciation was thus merely a superficial trigger for the subsequent events.

It was not ideological motives but rather the efficiency-driven technocracy of the Armaments Ministry that ultimately wrested control of the company from Johannes P. Vielmetter. Speer’s chief advisor, Karl Maria Hettlage, in a discussion with Knorr-Bremse’s supervisory board chairman, asked for Johannes P. Vielmetter’s resignation to be initiated “without any public fuss.” This led to Vielmetter stepping down on September 15, 1943, after more than 36 years on the executive board. Simultaneously, Otto Leibrock joined the board. As a legal advisor, head of the economic department, and Vielmetter’s assistant, Leibrock had been with the company since 1924, along with Friedrich Hildebrand and Kurt Anhalt.

In reality, Vielmetter’s grip on the reins of Knorr-Bremse had been slipping. The once tightly managed organization showed significant coordination deficiencies under the pressure of the wartime economy. Even Vielmetter’s secretary eventually held a kind of departmental authority, which, at least in the eyes of the supervisory board chairman, cost the company millions. Seeking a solution, the departing patriarch decided to appoint a leader with extensive powers at the helm of Knorr-Bremse. Despite numerous objections, he succeeded in installing Alfred Woeltjen as chairman of the executive board, granting him “decision-making authority in the event of disagreements.”

However, even the new strongman was unable to impose tight leadership on the increasingly embattled company. Woeltjen was held primarily responsible for the declining production and the resulting financial crisis at Knorr-Bremse. When the 84-year-old Johannes P. Vielmetter died on May 6, 1944, a few months after stepping down and while serving as honorary chairman of the Knorr-Bremse supervisory board, the situation spiraled out of control. The new operations director Walter Nase’s calls for an end to the “total in-house war” went unheeded. In May 1944, Woeltjen was stripped of financial responsibilities. Clinging to Vielmetter’s legacy, the increasingly isolated chairman of the executive board stubbornly remained in the role until April 13, 1945, when he was unceremoniously ousted from his office. By then, Berlin was under constant bombardment by Soviet artillery.

Beneath these personnel conflicts lay a deeper crisis, one that gradually engulfed the company as the war dragged on. Despite the growing shortages of labor and raw materials, Knorr-Bremse managed to continuously increase production until 1943. Total sales rose from RM 41.3 million in 1938 to RM 98.2 million in 1943. However, in the fall of 1943, due to bomb damage and production relocations, a persistent decline in production output, and consequently sales, began. This led to financial distress, exacerbated by the inability to collect significant receivables. Knorr-Bremse’s debts to Deutsche Bank took on ever more worrying proportions. Given the wartime economic circumstances, these problems did not yet have any far-reaching consequences. However, Deutsche Bank’s supervisory board chairman, Fritz Wintermantel, made it clear to the executive board in August 1944 that it would not extend the already exhausted credit lines any further. Research and development, a crucial factor for the company’s future, became more and more difficult to conduct.

The war began to take its toll on Knorr-Bremse. Starting in early 1943, the Berlin plant was repeatedly hit by air raids. On May 8, 1944, an attack claimed eleven lives and left over a hundred injured. The company’s other facilities also suffered bomb damage. On the night of March 8, 1943, approximately 600 incendiary bombs fell on the Südbremse plant, destroying, among other things, the engine testing facility. The branch plant of Carl Hasse & Wrede in Britz was half-destroyed by incendiary bombs on January 30, 1944.

The growing threat to the facilities spurred feverish efforts to find alternative locations. A proposal to move into the world-famous Meissen porcelain factory in November 1944 was abandoned due to its cramped layout. Similarly, a plan to set up alternative production in evacuated Dresden museums was fortunately never realized; Dresden was obliterated by Allied bombing during the night of February 13, 1945. Süddeutsche Bremsen, on the other hand, found a closer refuge from the hail of bombs that ravaged German cities in the final years of the war. In the empty beer cellars of the Franziskaner brewery, it set up a second plant to produce pumps for aircraft engines.

As the Red Army advanced, Knorr-Bremse lost its most valuable machinery at its relocation sites in Myszków and Sosnowiec. On January 20, 1945, 300 employees from Berlin and 100 foreign workers began a ten-day march from Sosnowiec to Berlin. Meanwhile, despite official prohibitions, thoughts turned to transitioning to peacetime production. The company placed hope in selling pneumatic-powered demolition hammers. On March 12, 1945, the executive board decided to remain in Berlin even in the event of the city’s capture by the Red Army, as moving the heavy machinery westward was far more difficult than relocating assets such as securities from Deutsche Bank’s vaults. Deutsche Bank had already decided to set up a backup headquarters in Hamburg.

Its board member Fritz Wintermantel, who had succeeded Gustaf Schlieper as supervisory board chairman after Schlieper’s death in 1937, was also the executor of Johannes P. Vielmetter’s estate. As bomb alerts increasingly disrupted factory operations, the company gradually prepared for “Day X.” Special orders were brought in to keep the remaining skilled workers from being drafted into the Wehrmacht or the national militia. Five days before the plant’s capture by the Red Army, the supervisory board chairman urged the company not to neglect the production of peacetime goods in anticipation of the months ahead.

In a Christmas 1944 letter to Vielmetter’s grandson and designated successor, who was in active military duty, Wintermantel wrote:

“Let us hope that during the coming year, the peaceful sounds of reconciliation will ring out, announcing a good peace. Stay healthy and enterprising; you will have endless opportunities to devote yourself to great tasks.”